- +1

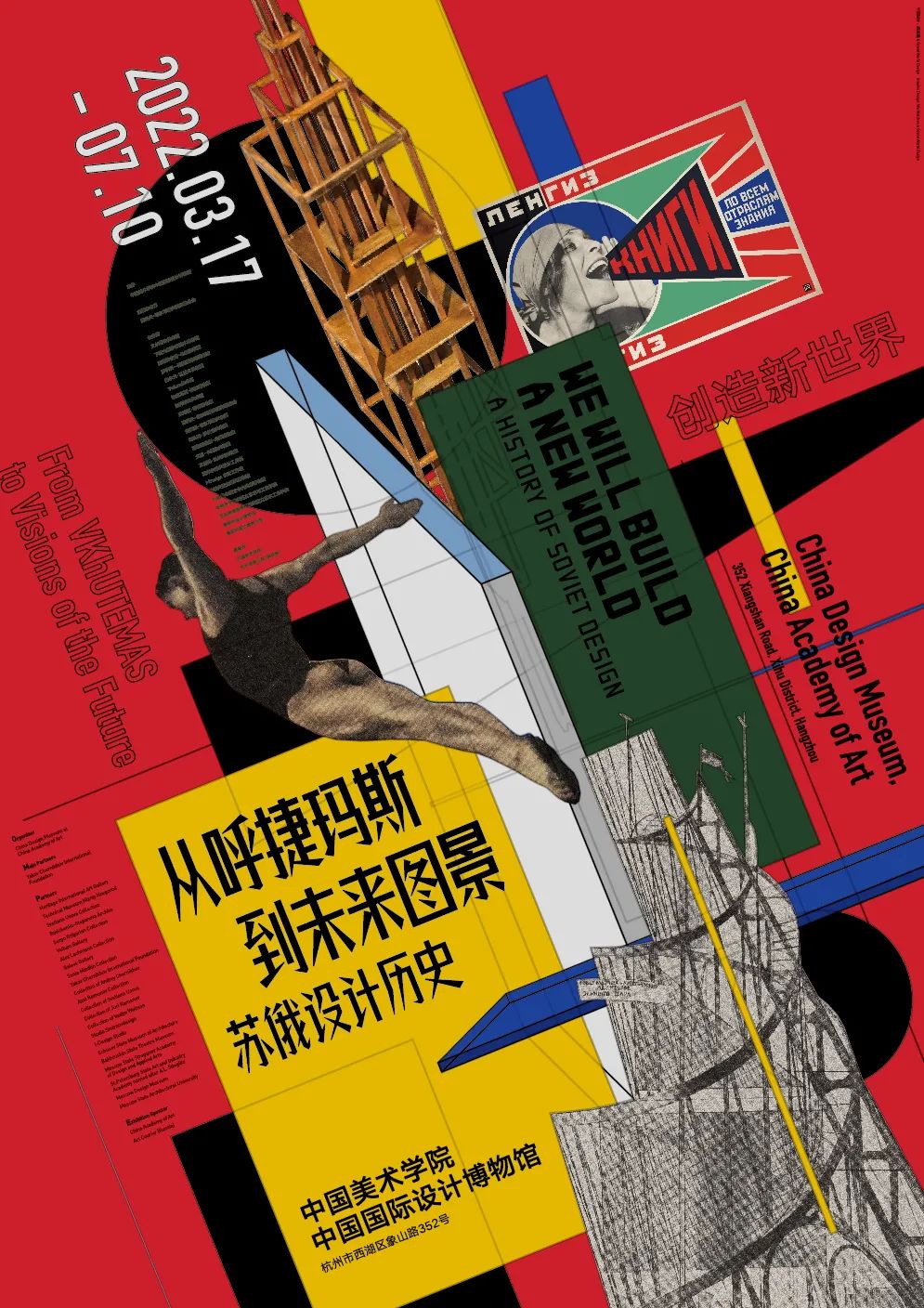

5·18国际博物馆日|特展“从呼捷玛斯到未来图景——苏俄设计历史”

展览|从呼捷玛斯到未来图景:苏俄设计历史

Exhibition|From VKhUTEMAS to Visions of the Future: A History of Soviet Design

展览时间|2022年3月17日—2022年7月10日

Period|17th March, 2022 - 10th July, 2022

展览地点|中国美术学院中国国际设计博物馆7、8、9号展厅

Venue| 7\8\9 Hall, China Design Museum at China Academy of Art

展览简介

展览聚焦于苏俄至苏联时期的设计创新,是中国国内第一次大规模展出该时期完整的设计历史,旨在探讨该时期的设计为构建全新生活世界所实施的先锋实验及其取得的成就,溯源设计和艺术领域的内生动力和创造力。

该项目自2019年启动,由中国美术学院中国国际设计博物馆与超过23家国际机构合作完成。展览所呈现的作品类型涵盖该主题相关的戏剧、建筑、手工艺,以及产品、平面、服装、交通等大部分现代设计门类。

展览由中外策展团队共同策划,聘请国际专家学者作为展览学术顾问,国际专家包括一流设计学院、博物馆的专家。

前言|从呼捷玛斯到未来图景

——高世名

From VKhUTEMAS to Visions of the Future by Prof. Gao Shiming

二十世纪上半叶,共产主义理想是推动现代艺术革命最强大的精神动力,以创造一个自由、平等、进步的新世界为愿景,激励着大批先锋艺术家投身左翼文化运动和国际共产主义运动。

以至上主义、构成主义等为代表的苏俄先锋派,是现代艺术的重要源头,也是社会主义文化的重要组成部分。彼时,“构成”与“抽象”作为革命的艺术语法,成为一种创造新世界的理念和力量。瓦西里·康定斯基(Wassily Kandinsky)、卡兹米尔·马列维奇(Kazimir Malevich)、埃尔·利西茨基(El Lissitzky)和弗拉基米尔·塔特林(Vladimir Tatlin)等一批深受革命感召的先锋艺术家们,否弃一切布尔乔亚式的唯美与矫饰,拒绝所有世俗化的再现与个人化的表现,试图建构一种精神性的、人民的新文化。对马列维奇来说,这种新文化是一种“非客观的至上主义”,其目的是建构最纯粹的精神图式。而在亚历山大·罗钦科(Alexander Rodchenko)和利西茨基看来,还有一种伟大的力量来自社会化工业大生产、来自无产阶级劳动者的集体性制作。于是,个体主义、自由主义的创造性假设被打破了,握着画笔的艺术家之手与生产线上操作机器的劳动者之手联接在一起,这个社会性的“创作集体”将以不假装饰的简洁与诚实,为构筑一个平等的新社会而服务。

1920年代,一批极具先锋精神的艺术家、建筑师、工程师、诗人汇集在一所伟大的学校 —— 呼捷玛斯(VKhUTEMAS)。他们将纯艺术(Fine Art)转变成设计、技术和日常劳作。他们的梦想是用自己的创作与教学进行一场审美、伦理、政治的总体性社会实验。他们带着重塑艺术本体的力量、重新发明世界观的雄心,试图建构一种未来图景,一种全新的秩序和经验。他们不止创造了建构性的艺术、生活的艺术,而且企图发动一场针对感性结构和艺术生产的更为深刻的革命,重组我们的欲望机制和社会形式。

然而,在1950年代之后的艺术史流行叙事中,以抽象艺术、未来主义、表现主义、超现实主义为主体的先锋艺术逐渐由曾经“革命的艺术”转向“自由的艺术”,其发生和发展的革命动因和价值理念被遮蔽了。于是,罗莎·卢森堡(Rosa Luxemburg)纪念碑、苏维埃戏剧节的设计图纸被“作品化”,被装上画框,作为欧洲抽象艺术的支脉,挂在现代艺术博物馆的墙上。它们的社会脉络被切断,它们的意义和功能被抹去,它们的革命性被掏空,它们成为了脱离历史的“无题”。在这种戏剧性的历史反转背后,是一种“文化冷战”机制。这种机制及其精神构造在国际文艺界中影响深远,作为二十世纪的“遗产”或“包袱”,至今仍未得到深刻反思和系统清理。通过这个展览,一些尘封半个多世纪的艺术线索被初步钩沉起来,苏俄先锋派艺术和社会主义设计依稀显露出其历史容颜。

一百年过去了,这些激进的形式创造和社会实验已成过往,然而我始终相信,百年前那个创造新世界的未来图景,是世界史与艺术史中一项伟大的未竟之业。百年后的今天,这个图景的潜能与势能正在重新凝聚,那个失落的世界、那段被遗忘的历史,正等待着被重新唤起。

中国美术学院 院长

高世名 教授

2022年3月23日

During the first half of the 20th century, the revolutions inspired by the ideal of Communism was the most powerful spiritual driving force for the modern art. With the hope of creating a free, equal and progressive new world, a wave of avant-garde artists threw themselves into left-wing cultural movements and the International Communist Movement.

The Soviet Russian avant-garde, most famously represented by Suprematism and Constructivism, was an important source of modern art, as well as a significant component of the Communist culture. As the revolutionary art language, “construction” and “abstraction” became the ideology and power behind the creation of a new world. Deeply influenced by the Soviet Revolution, a whole generation of artists like Vassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, El Lissitzky and Vladimir Tatlin repudiated and abandoned the bourgeois aestheticism and mannerism. They refused all re-occurrences of secularity and behaviors of individualism, in an attempt to build a new intellectual culture that belonged to the people. For Malevich, this new culture was a type of “non-objective Suprematism,” whose purpose was to create the purest spiritual forms. Yet for Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, there was another powerful force that came from the socialized industrial production and the collective manufacturing by proletariat laborers. As a result, the assumption that individualism and liberalism led to creativity shattered. The artists’ hands holding brushes and the workers’ hands operating machines on production lines joined together: this social “creative collective” was ready to construct a new egalitarian world with concision and honesty, free of embellishment.

In the 1920s, a group of avant-garde artists, architects, engineers and poets came together at VKhUTEMAS, turning fine art into design, techniques and everyday labor. Their dream was to use their art and teaching to conduct a conclusive social experiment on aesthetics, ethics and politics. They carried in them a force that remolded the essence of art and an aspiration that re-invented a worldview. They tried to construct a future prospect, a new order and experience. They not only created constructive art—the art of life—but also attempted to start a more profound revolution directed at the perceptual structure and art production, re-configuring our mechanism of desire and the type of society.

However, in the popular narrative of art history after the 1950s, the avant-garde that comprises mostly of abstraction, Futurism, Expressionism and Surrealism slowly turned from the “revolutionary art” towards the“Free Art”, concealing the revolutionary causes and values behind its inception and development. Consequently, the design drawings of the Rosa Luxemburg Memorial and the Soviet Theater Festival were transformed as “art work” by framing, hung on the walls of contemporary art museums as a subsidiary branch of European abstract art. Their social context was cut off, their meanings and functions erased, their revolutionary characters hallowed out. They became the “untitled”, divorced from history. Behind this dramatic historical twist lies a “cultural cold war”, a mechanism whose spiritual fabric had a far-reaching impact on the international art and literature scenes. However, as a “legacy” and “baggage” of the 20th century, it has yet to be thoroughly reflected upon or systematically researched. This exhibition serves as a preliminary examination of this thread that has been dust-laden for over half a century, allowing the Soviet avant-garde and the design in Socialist period to reveal their foothold in history.

A hundred years later, those radical form-making and social experiments are in the past, yet I believe that the century-old prospect for the new world remains a grand unfinished mission in the world history and in the art history. A hundred years later, the potential for this prospect is re-charging; That lost world and forgotten histories are waiting to be re-conjured.

Professor Gao Shiming

Rector

China Academy of Art

Mar.23, 2022

1

新的世界观

NEW WORLDVIEW

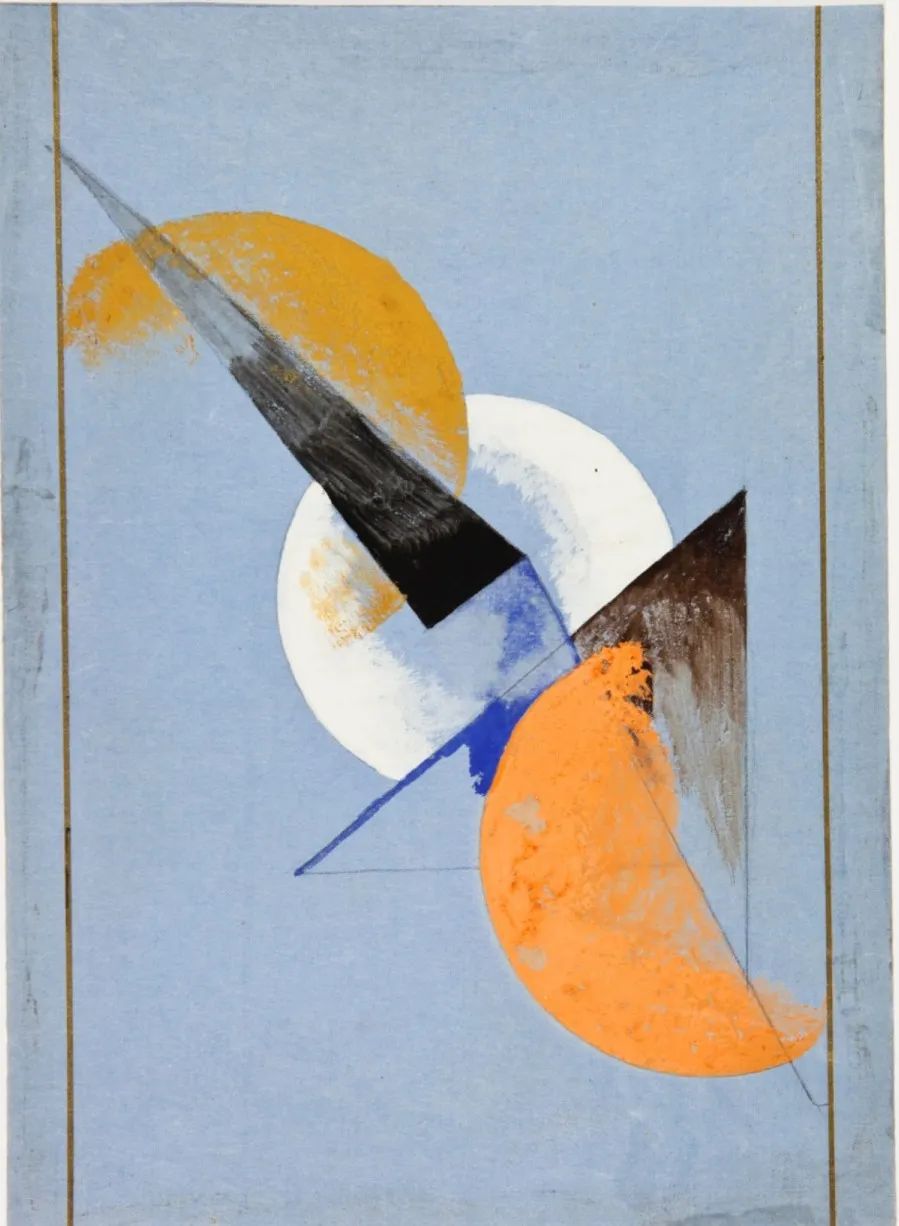

在20世纪初,科学与技术吸引了大量艺术家。物理学、天文学、生物学、心理学和逻辑学中的新发现挑起了许多人的兴趣。抽象的、哲学的、高度概括的有关世界及其规律的理解成为了绘画实验、图形实验的内容。正像亚历山大·罗钦科(Alexander Rodchenko)曾宣告的:“构成就是现代的世界观”。彼时,先锋派所倡导的生产艺术运用了工业技术、自动几何图形复制技术来进行实验。这些实验的影响都可见于后来亚历山德拉·埃克斯特(Aleksandra Ekster)、瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷帕诺娃(Varvara Stepanova)的染织作品,卡兹米尔·马列维奇(Kazimir Malevich)、尼古拉·苏耶金(Nikolai Suetin)、伊利亚·恰什尼克(Ilya Chashnik)的陶瓷作品,以及城市的节日装饰设计、平面设计和报亭、展厅、剧院的设计。由于种种原因,这些先锋设计作品虽然大部分未能以物质形态留存,但在其影响下,人们发现了一种认识世界的新路径,深刻塑造了20世纪乃至今天的设计。

At the beginning of the twentieth century, artists were fascinated by science and technology. Many were interested in new discoveries being made in physics, astronomy, biology, psychology and logic. As a result an abstract, philosophical, and extremely generalized view of the world and its laws became the content for their pictorial and graphic experiments.

In 1920, the artist and designer Alexander Rodchenko proclaimed “Construction is a modern worldview”. At the same time, Russian Productive Art sought the technical industrial reproduction of a composition, such as the replication of relatively autonomous geometric images, as can be seen in the textile designs of Aleksandra Ekster and Varvara Stepanova, the porcelain of Kazimir Malevich, Nikolai Suetin,and Ilya Chashnik, as well as in the festive decoration of cities, typography, kiosk designs, exhibition pavilions, and theater designs. For various reasons, most design works created by the avant-garde could not tangibly survive. But the modern worldviews generated by such design have had a profound influence on the world for a very long time.

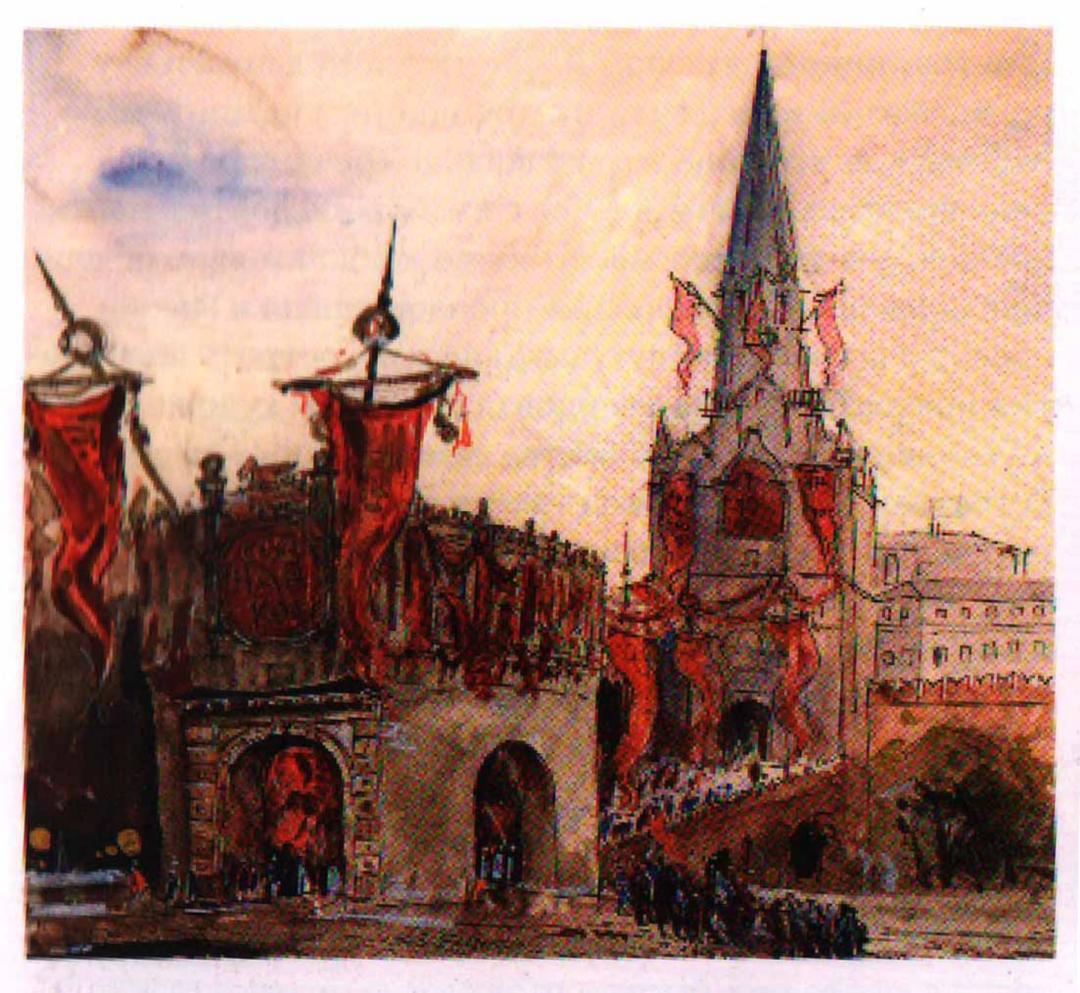

В.А.维斯宁,А.А.维斯宁

“1918 年五一劳动节前夕克里姆林宫与红场设计项目:克里姆林宫泰尼茨基门与库塔菲亚塔风景草图”

1918年

伊万·普尼

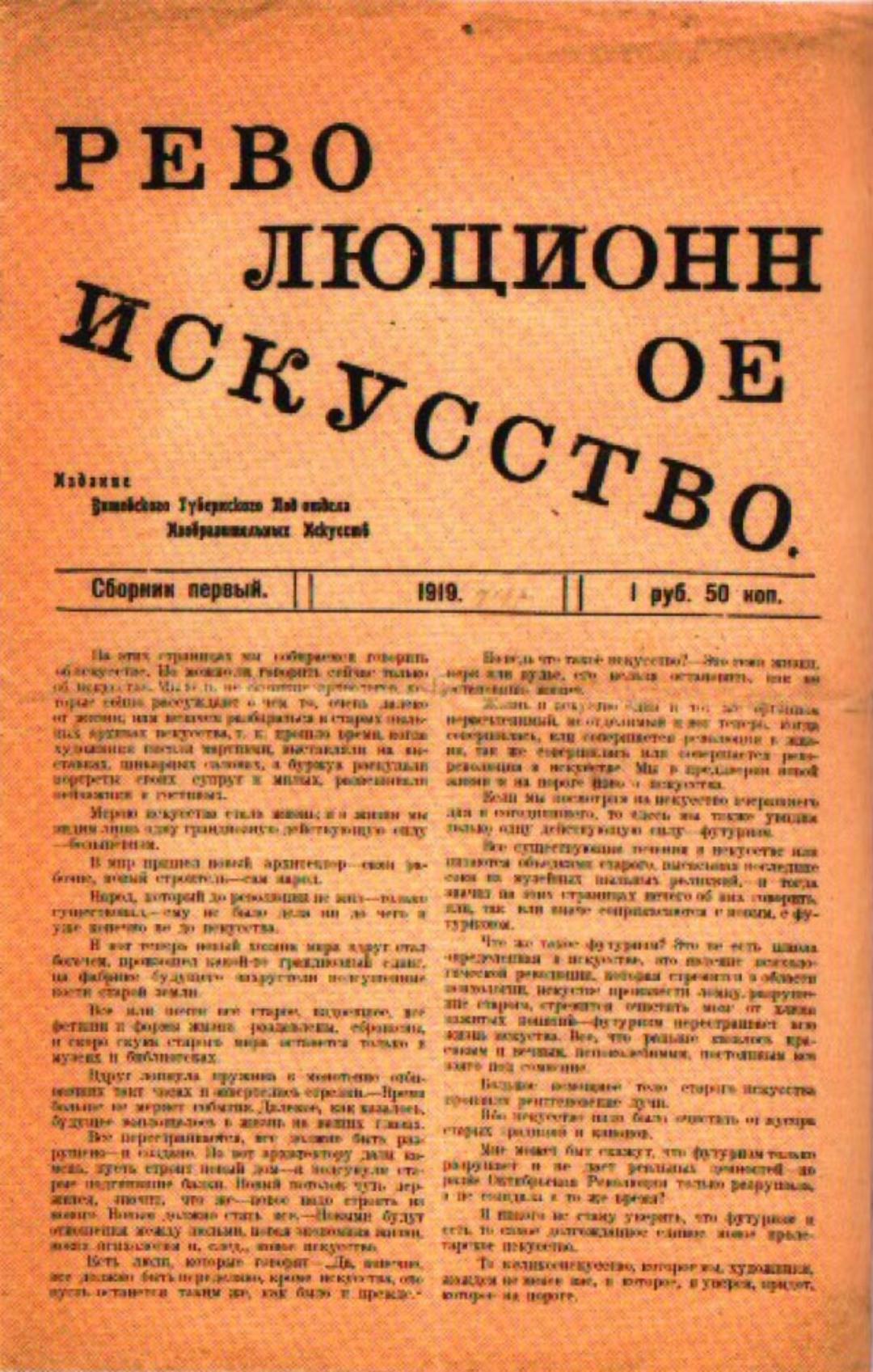

“革命的艺术”第一期,4月24日,1919年

埃尔·利西茨基

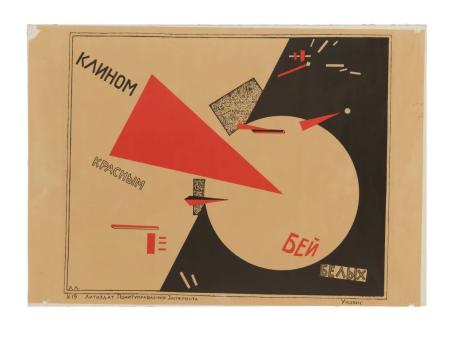

“用红色楔形打败白色”石版画1920年

2

呼捷玛斯

VKhUTEMAS

1920年12月19日苏联人民委员会下令在皇家斯特罗加诺夫学校和绘画、雕塑与建筑学校的基础上成立“呼捷玛斯”(国立高等艺术与技术工作室),旨在为工业发展培养高水平的艺术家,为艺术技术的教育培养教员。整个呼捷玛斯,是革命后新社会体制的产儿。重新建立的国家生活、一系列被打开的可能以及高等艺术学校所面临的完全崭新的任务,要求高等艺术院校不仅重新审视教学的目标、教学大纲和方法,还必须重新审视和解决一系列普遍的、原则性的问题。事实上,包含了从高等艺术教育到大众普通艺术教育的新教育模式蓝图早在1918年就已经由人民启蒙委员会艺术分部编订,并同时被刊登在国内外的媒体上,对世界艺术和设计教育的改革产生了深远的影响。

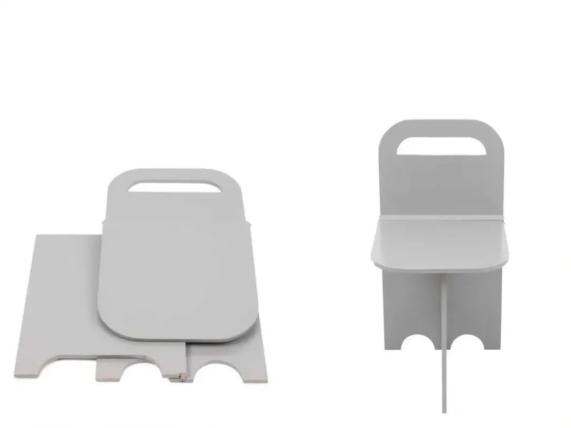

先锋派在实验中运用的形式分析法成为了该校在有关空间、体积、色彩、图形的课程中开展抽象训练的基础。在基础部的学习之后,学生会分流到8个系,即建筑系、绘画系、雕塑系,以及各个生产系,即金工系、木工系、陶艺系、染织系、印刷系。生产系的专业课程就是设计方案。生产系特别重视创造力,比如重视将多种功能结合到一个物件中,组合拆解的动力学,简单明了的几何图形,并通常会研究设计多功能、轻便的物件。学生还经常会参与到自己导师实际的项目中,如创作新型的广告;为标准型的公社之家设计家具,装饰公园等。

生产系毕业生被称为“工程艺术家”或“艺术工艺师”,并会被标明是哪一个工业领域的专业人员(木工或金工、染织、陶艺和印刷),他们在生产中担任“艺术家导师”“艺术家组织者”的角色。

VKhUTEMAS (Higher Art and Technical Workshops) was created by a decree from the Council of People's Commissars on December 19, 1920, and was formed from a merger between the Stroganov School of Applied Arts and the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture and was focused on the training of highly qualified “artists for industry” (designers) as well as teachers specializing in art and technical education.

The VKhUTEMAS was a result of the introduction of a new post-Revolution social system. By re-establishing national life, a series of possibilities opened up, and the completely new tasks faced by higher art schools required not only the re-examination of the goals, syllabus and methods of teaching, but also the re-examination and resolution of a series of universal principles. In fact, the "blueprint" for a new educational model, from higher art education to public art education, was published by IZO-Narkompros (the Department of Fine Arts of the People's Commissariat for Education) in 1918, and was concurrently widely published within the media both at home and abroad. This “new model” has since had a profound impact on the reform of world art and design education.

For instance, the formal analytical method, devised by Russian avante-garde artists through experimentation became the basis for creating abstract exercises relating to the disciplines of Space, Volume, Color, and Graphics.

After undertaking the introductory course, students went on to train in either the architecture, painting or sculpture faculties, or in one of the production workshops for metalwork, woodworking, ceramics, textiles, or printing (graphic design).

Innovation was especially appreciated, especially in relation to: the combining of functions in a single object; the kinematics of folding and unfolding an object; simple and geometrically clean forms; and multi-functionality. Often, students participated in the real-world projects of their leaders/teachers–they helped to create “new” advertisements, developed furniture for model social housing, and decorated public parks.

Graduates from the so-called production faculties received the title of "artist-engineer" or "artist-technologist" indicating their specialization within their specific industry (wood or metalworking, textile design, ceramics or printing). They were supposed to go on to become art directors, or artistic managers within factories.

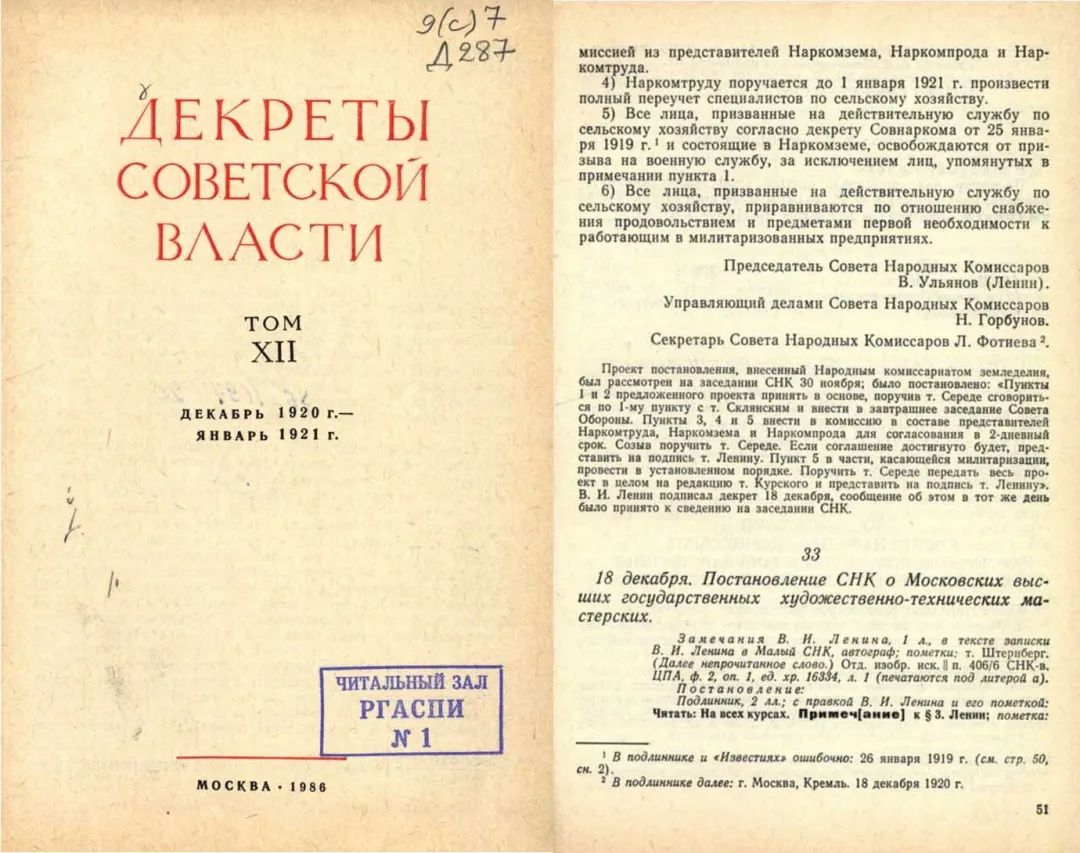

苏俄人民委员会 (SNK)

1920年12月18日人民委员会关于莫斯科高等国家艺术和技术研讨会的法令-苏维埃政权法令-档案第12卷封面和第51页

亚历山大·维斯宁

“十月革命十周年呼捷玛斯大楼装饰工程”

1927年

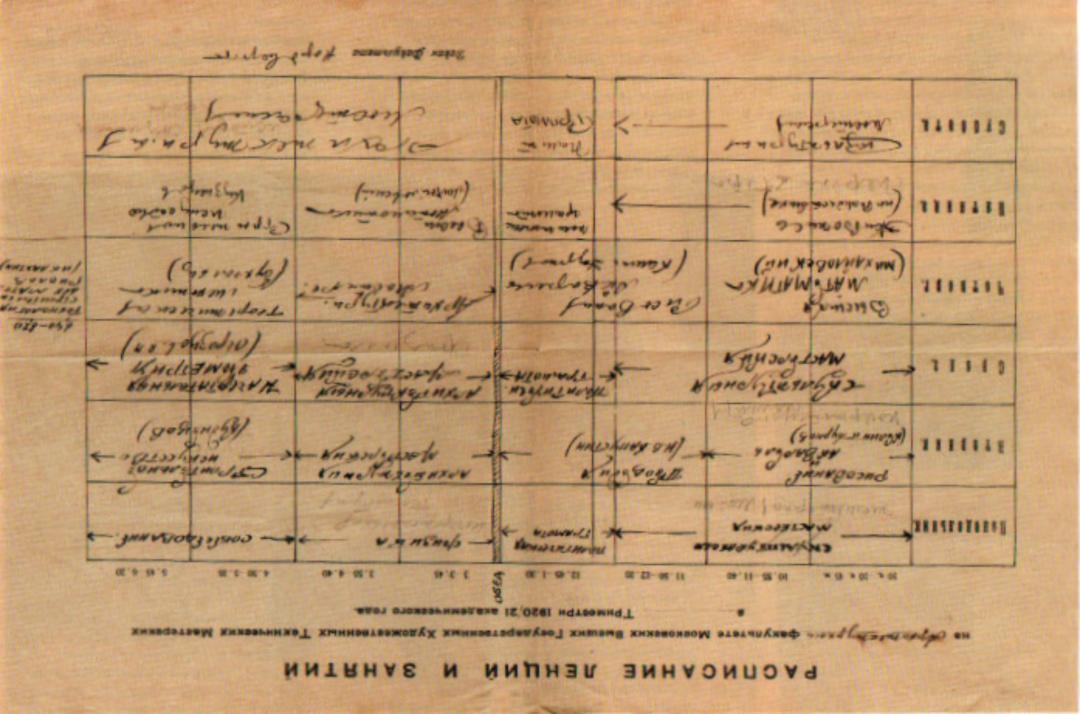

呼捷玛斯学院的1920/1921学年建筑系课程表

1920年

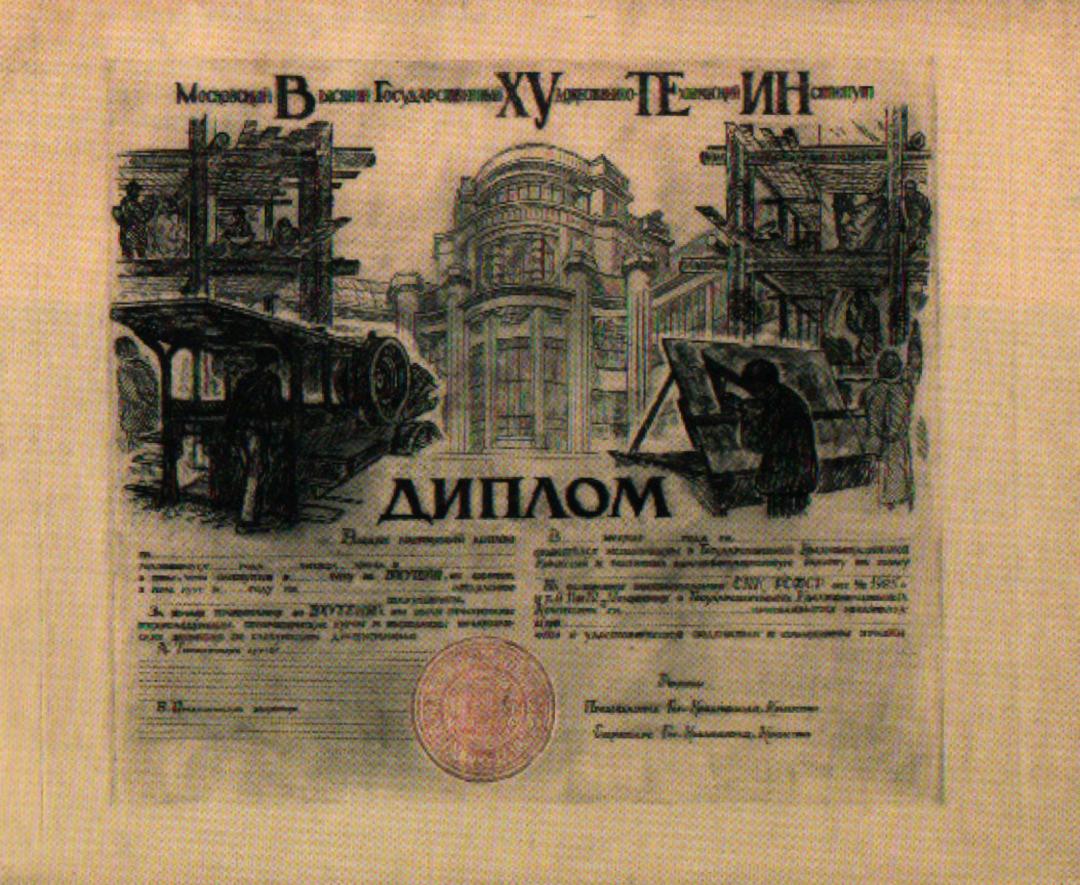

呼捷玛斯学院毕业证书,测绘系V. 拉宾

1928年

呼捷玛斯学院的学生举着旗帜在游行照片

1923年

用于游行的呼捷玛斯学院共产主义支部旗帜的草图

1923年

呼捷玛斯毕业生亚·亚历山大·维斯宁(左),伊凡·列昂尼多夫(中)和 伊·雷利斯基(右二)与建筑系学生 照

1920年代后期

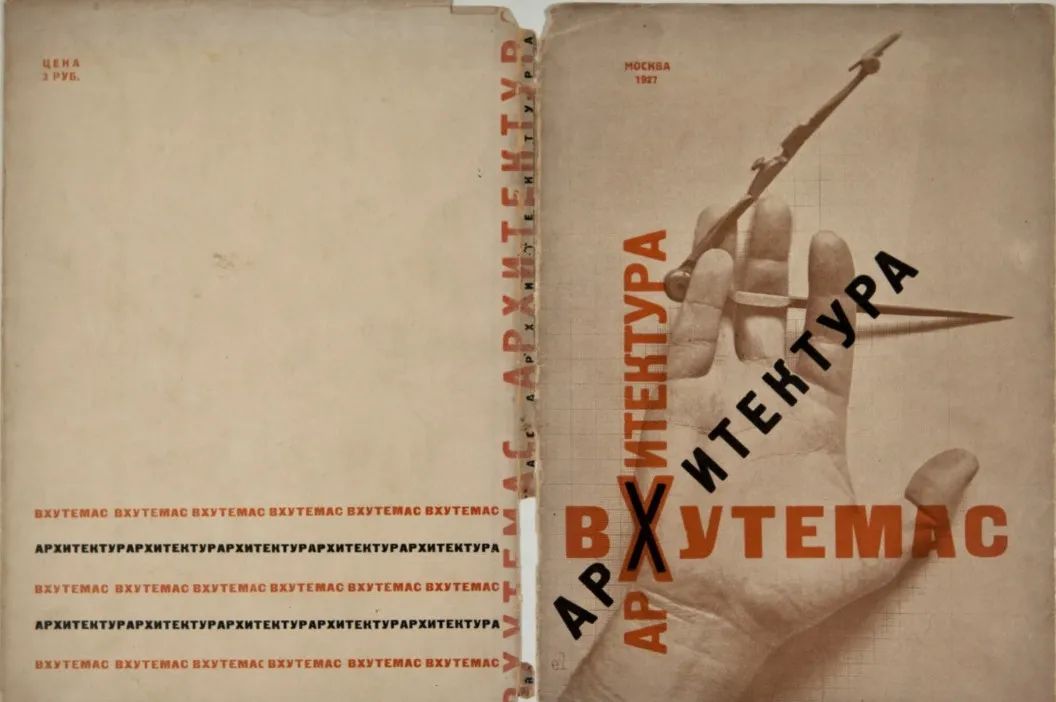

呼捷玛斯学院建筑教学成果集

1927年

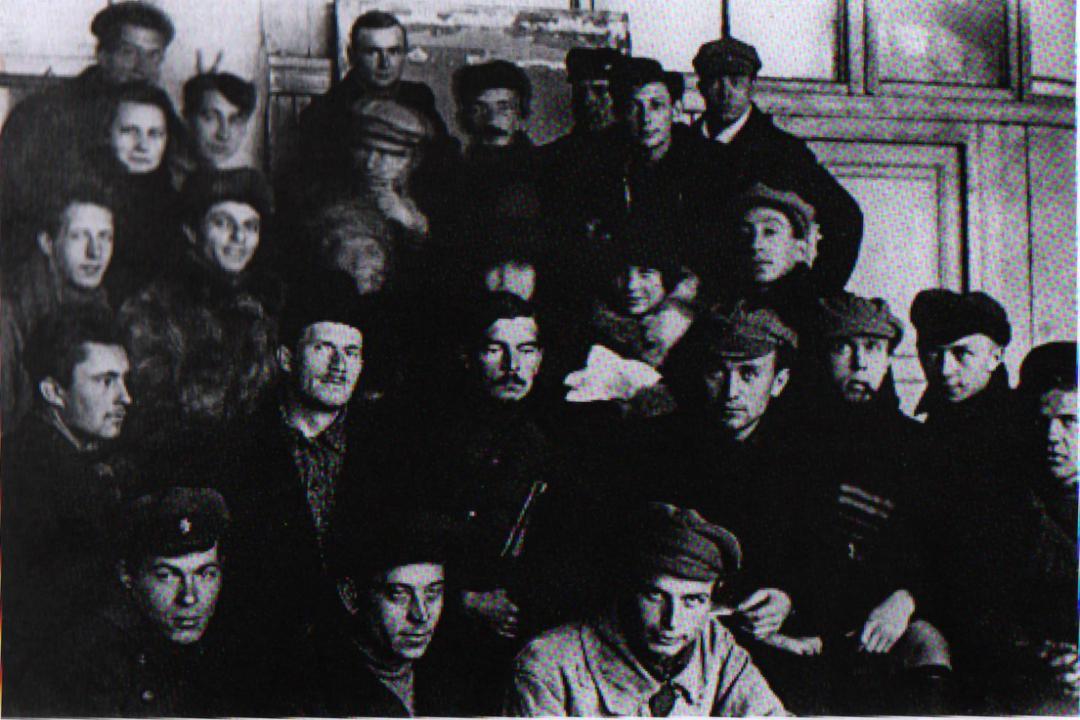

“呼捷玛斯联合研讨会学生和建筑师合影”

第一排:伏·叶尔绍夫,亚·西利琴科夫(?),瓦·尼·西姆比尔采夫

第二排:尼·克拉西利尼科夫,尼·亚·拉多夫斯基,阿·米·鲁赫利亚杰夫,伊·瓦·拉姆佐夫,S·洛帕京,G·马克延科,I·格鲁申科

第三排:尤·斯帕茨基,L·布马日内,R·别尔林,莉·科马罗娃,柳·扎列斯卡娅,I·约瑟夫维奇

第四排:未知,V·彼得罗夫,伏罗洛夫(?),伏·费·克林斯基,无名氏,尤·穆辛斯基,米留京

最上排:无名氏,伊·约·沃洛季诺

1920年代中期

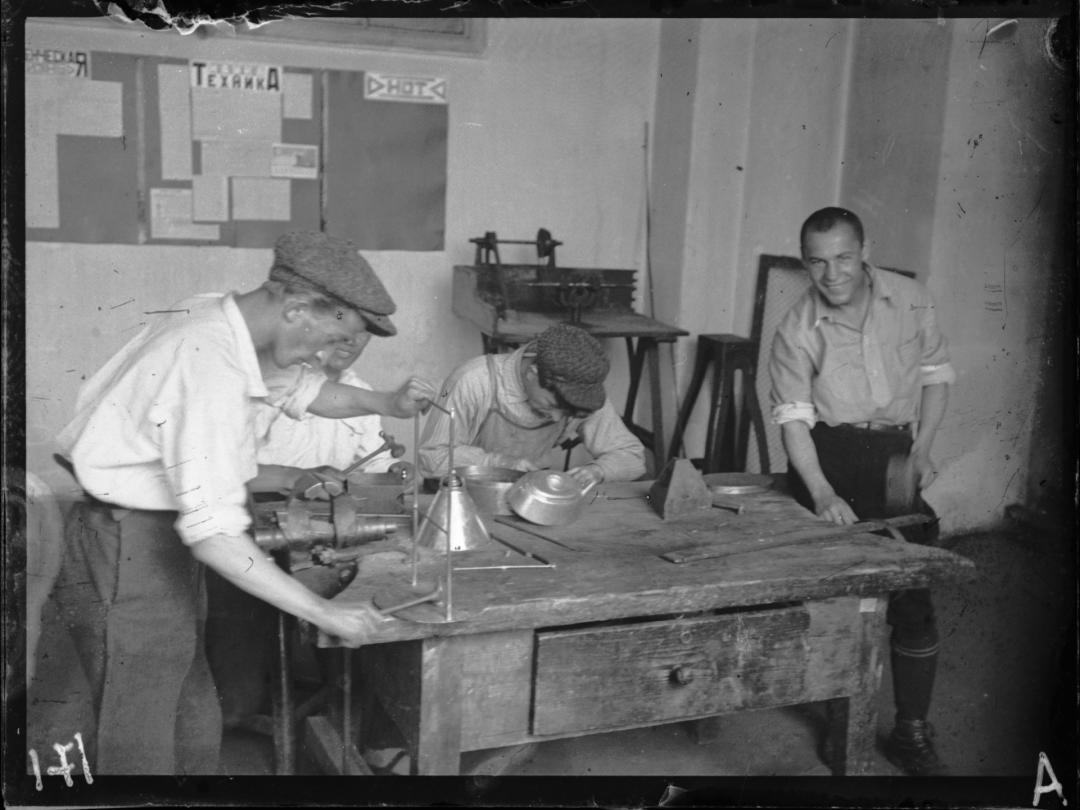

呼捷玛斯的金属课程场景

从左至右:日古诺夫(加工自己的转灯)、莫罗佐夫、帕甫洛夫、贝科夫。右边桌子上是贝科夫茶壶小锅的零件

1924年

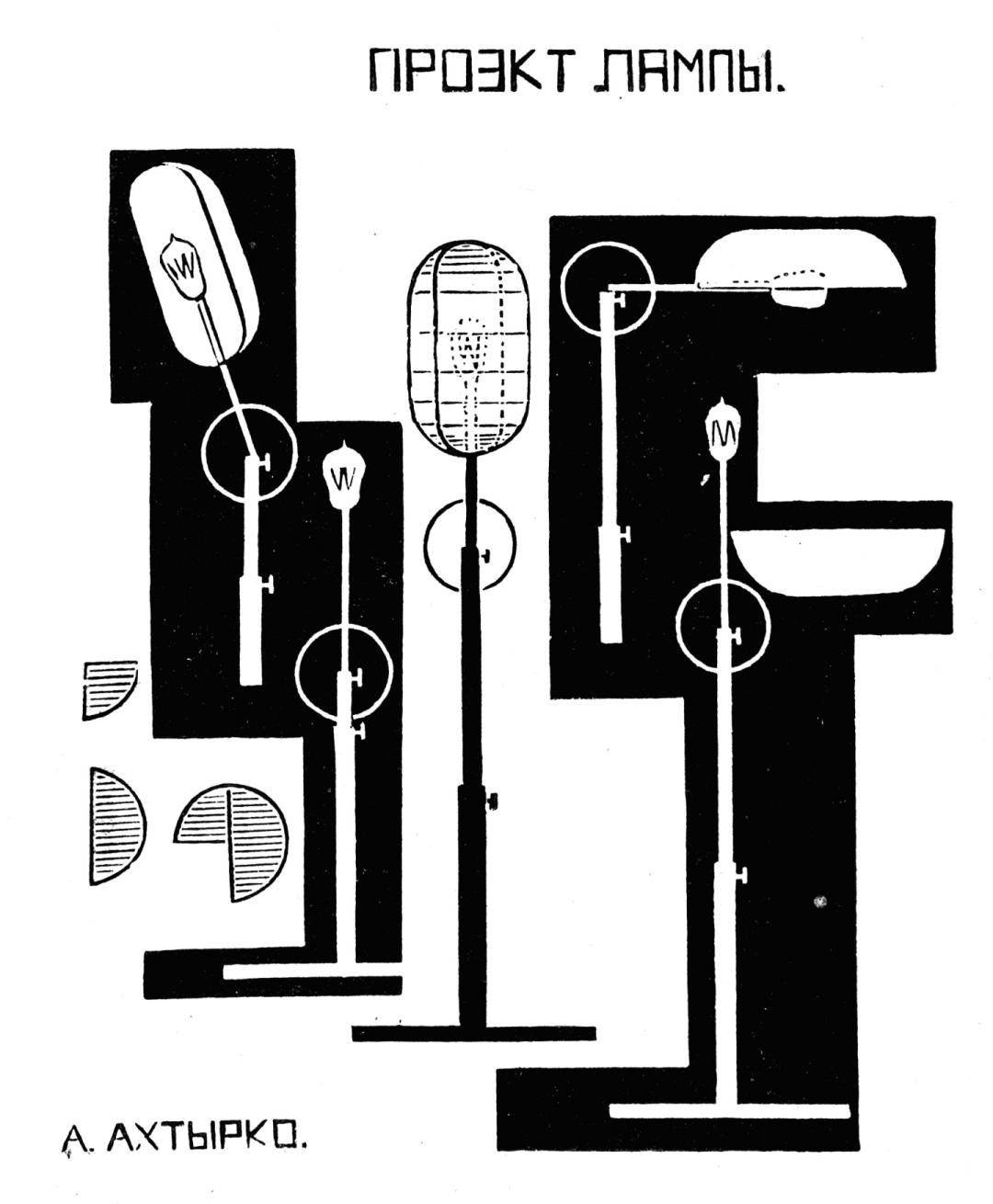

А. И. 阿赫特尔科、亚历山大·罗钦科

落地灯的设计(一种方案)

1922年

扎哈尔·贝科夫

可调节角度吊灯

1922年

呼捷玛斯的木工作坊课程场景

1920年代

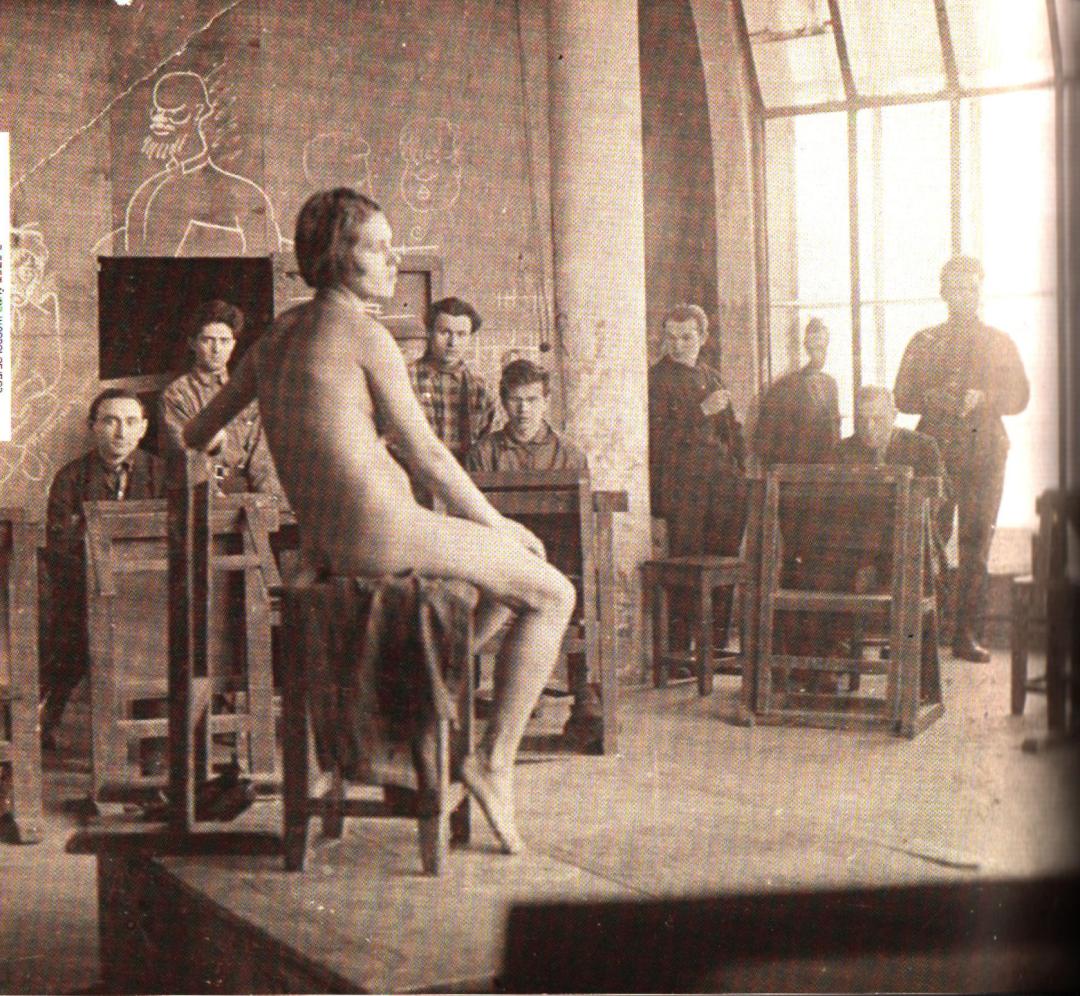

呼捷玛斯学院学生在绘画课上

1920年代初期

呼捷玛斯学院基础部礼堂内习作模型展示

1927-1928年

“呼捷玛斯基础部门教师在空间课上”

教师米·彼·科尔热夫(左二)、克·伏·克林斯基(中)、图尔库斯(右二)与学生们的照片

1920 年代中期

尼古拉·拉多夫斯基

呼捷玛斯“空间”课程作业——立体形式的表达

1920—1925年

亚历山大·罗钦科

空间构成

1920—1921年

尼古拉·拉多夫斯基

呼捷玛斯“空间”课程作业——立体形式、体量、重量的表达

1920—1925年

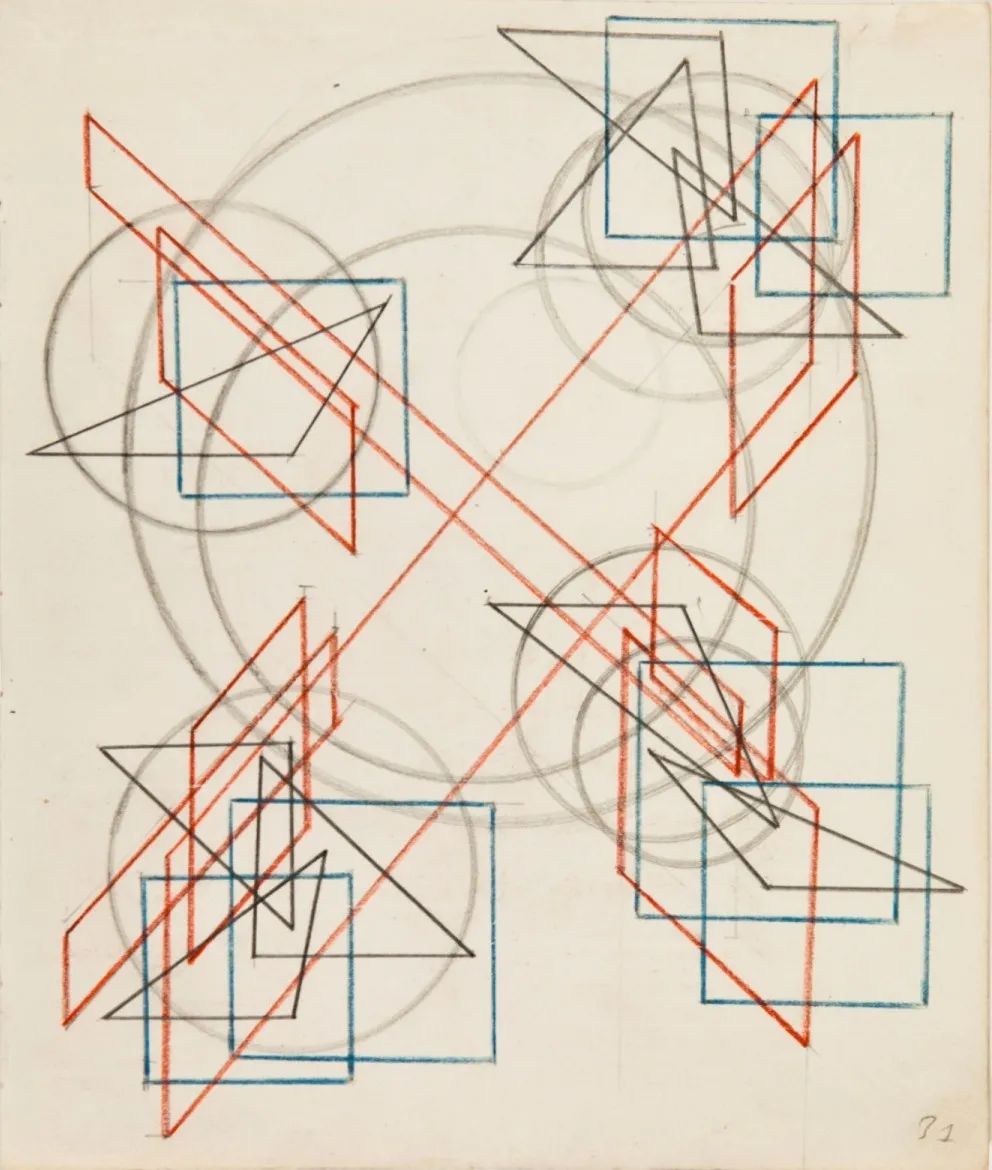

А. И. 阿赫特尔科

呼捷玛斯学院习作 几何形结构

1921年

А. И. 阿赫特尔科

颜色练习-在空间中消解形式

1921-1922年

3

工人文化

NEW PROLETARIAN CULTURE

1920年代开始,新生的设计和建筑、大众广告和宣传、电影和戏剧、批判庸俗习气的文学,所有这些都构成了新的工人文化,旨在培养“新人”。诗人阿列克谢·加斯捷夫(Aleksei Gastev)成为了世界上第一个“劳动学院”的校长,在这里工人们科学地研究在各个生产领域劳动操作的学习方法。加斯捷夫写道:“黑色的烟囱、厂房、摇臂、气缸。我准备好了与你们交谈,在你们的面前举起双手,歌颂你们,我的钢铁之友们……我走向工厂,就像走向节日的欢庆,走向盛宴”。

社会生活的组织,如食堂和工厂厨房、幼儿园、公社之家的建设都被赋予了巨大的意义。”工人俱乐部”杂志介绍了进步的戏剧演出剧目、俱乐部空间组织的案例和课程开展的范例。为了传播文化知识,人们采用“动态报纸”的形式,也就是一种基于政治时事的以宣传建造新世界为目的的戏剧化表演。“通过俱乐部走向新生活”,这样的口号往往被高挂在工人俱乐部的入口。

Since 1920s,the newly created school of design and architecture, mass advertising and agitation, progressive cinema and theater, articles about the fight against philistinism within everyday life - all this was aimed at educating a "new man". The poet Aleksei Gastev became the director of the world's first "Institute of Labor", where the methodology of teaching labor processes in various types of production was scientifically developed. "... black pipes, housings, connecting rods, cylinders. I am ready to speak with you, raise my hands in front of you, praise you, my iron friends ... I am going to the factory, as if for a holiday, as if for a feast," Gastev wrote.

Great importance was attached to the organization of social life: the organization of canteens and factory kitchens, kindergartens, and communal housing. The “Rabochy Klub" (Workers’ Club) magazine introduced the repertoire of progressive theatrical performances, explained how the club's spaces were organized, and provided examples of how its classes were conducted. To promote literacy and knowledge, the principle of a "living newspaper" was used-whereby theatrical performances were based on political news and agitation for the construction of a new world. The slogan“Through the club to a new way of life” was proposed to be hung in front of the club’s entrances.

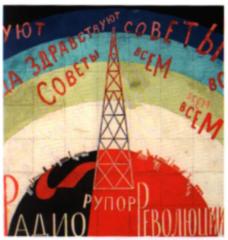

弗拉基米尔·克林斯基

“广播——革命的渠道:共产国际代表大会期间莫斯科工会大厦装饰”海报素描

1922年

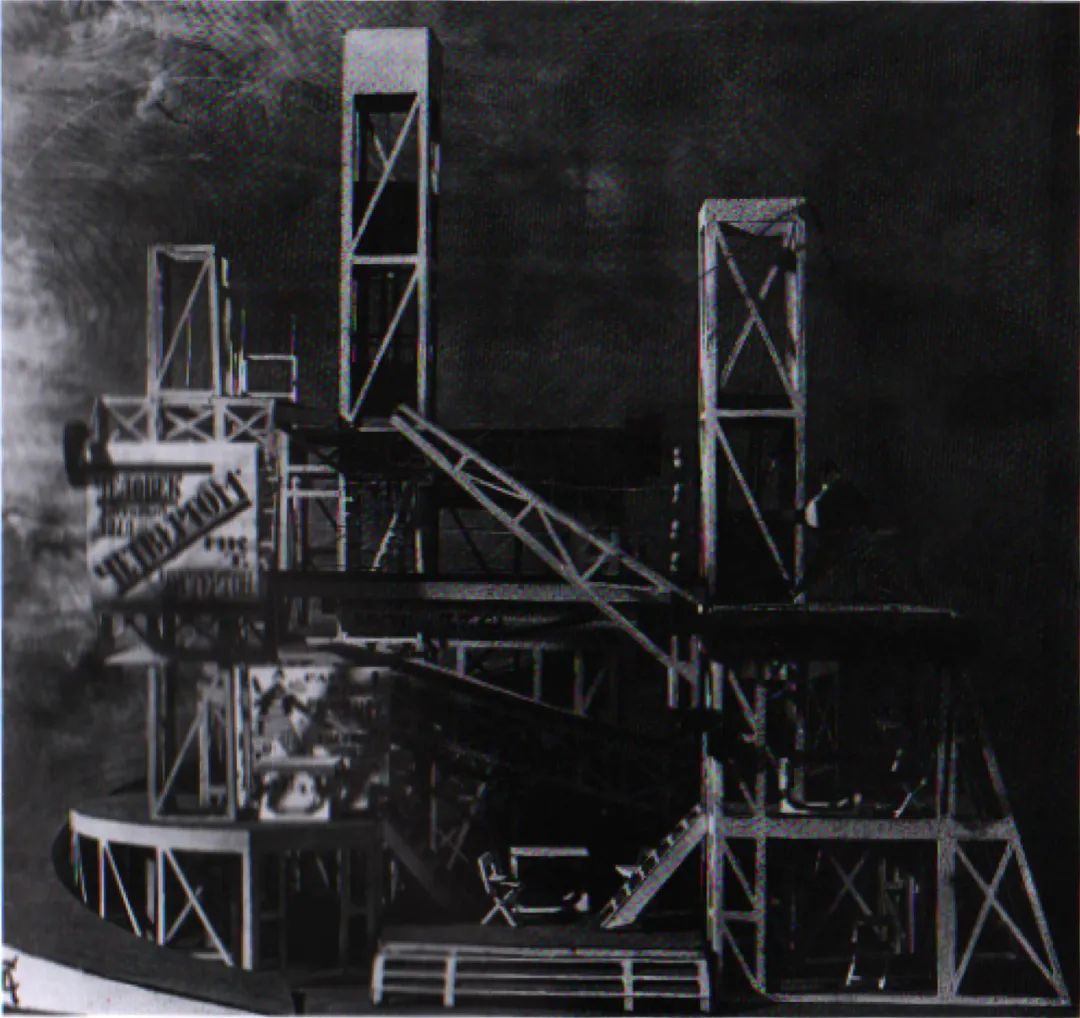

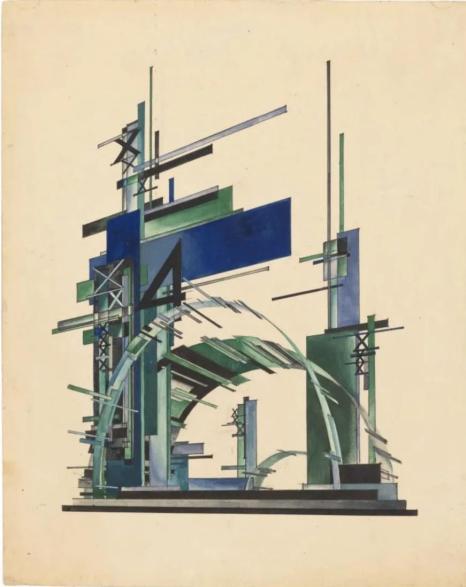

亚历山大.维斯宁

根据吉尔伯特·切斯特顿小说改编的戏剧《星期四的人》舞台布景

1922-1923年

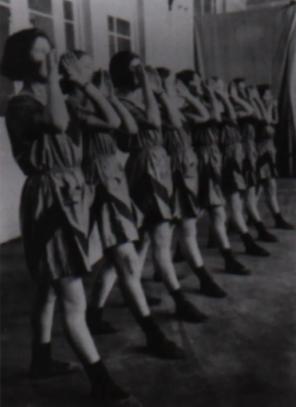

服装设计:瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃

“阅读晚会”俱乐部表演场景

1924年

弗拉基米尔·斯坦伯格与乔治·斯坦伯格兄弟

戏剧“圣女贞德”(根据萧伯纳戏剧改编)服装,骑士盔甲变成了产业工人工作服

1924年

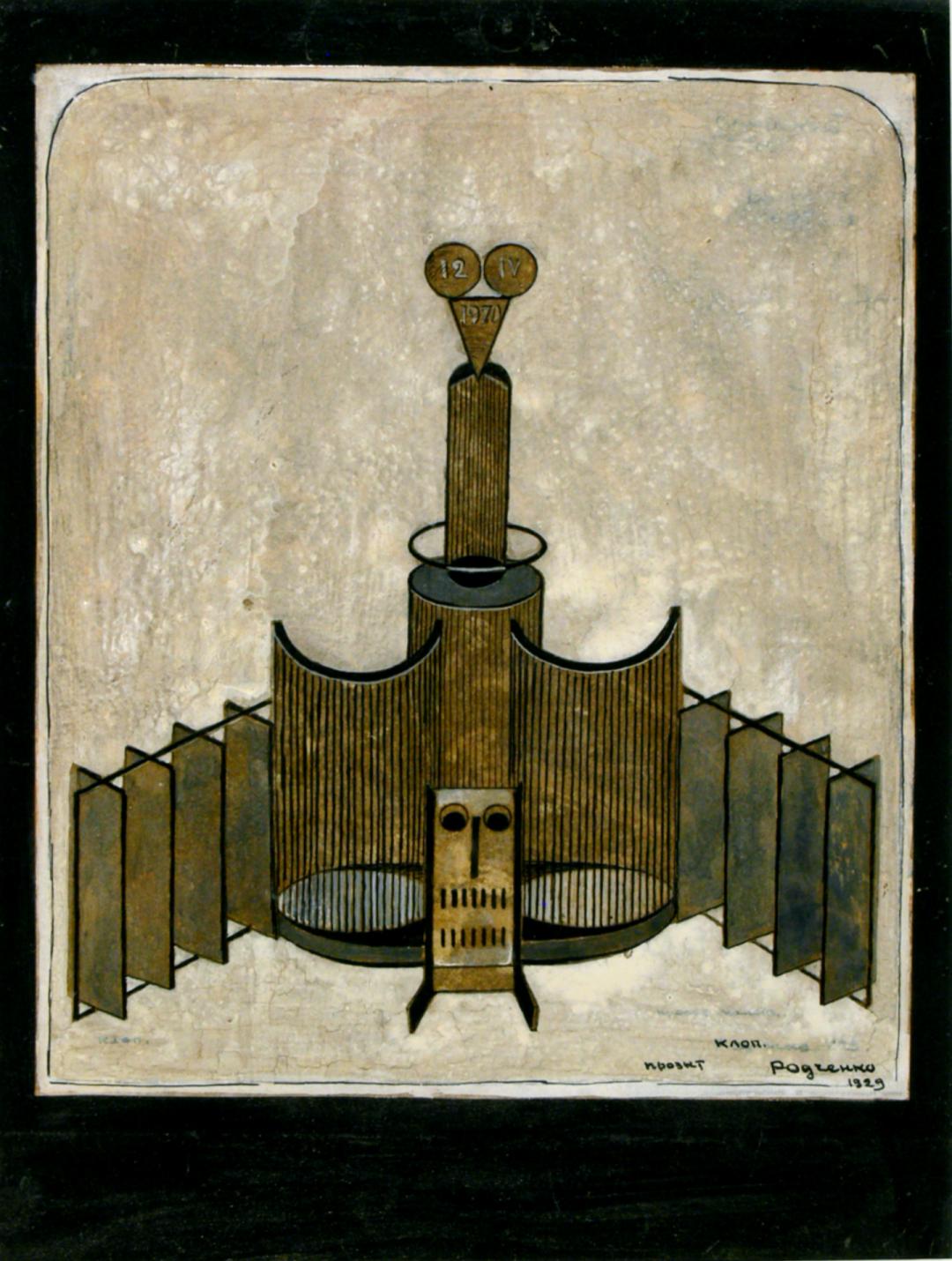

亚历山大·罗钦科

戏剧“臭虫”男性戏剧服装

1929年

亚历山大·罗钦科

为弗拉基米尔·马雅可夫斯基戏剧“臭虫”设计的舞台装饰之第二幕草图

1929年

弗拉基米尔·德米特里耶夫

为埃米尔·维尔哈伦戏剧“黎明”设计的舞台装饰

1920年

亚历山大.维斯宁

“让·拉辛戏剧〈菲德拉〉装饰”场景素描

1921年

亚历山大·罗钦科

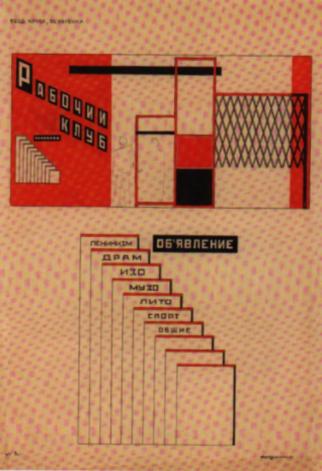

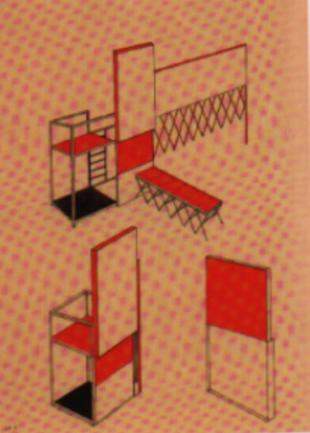

巴黎国际装饰艺术与艺术工业博览会工人俱乐部内景(朝向讲台)

1925年

亚历山大·罗钦科

巴黎国际装饰艺术与艺术工业博览会苏联展区的工人俱乐部设备草图

1925年

亚历山大·罗钦科

巴黎国际装饰艺术与艺术工业博览会苏联展区的工人俱乐部入口,墙体展开图,巴黎

1925年

亚历山大·罗钦科

国际装饰艺术与艺术工业博览会苏联展区的工人俱乐部的可变形讲台,巴黎

1925年

瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃(女式工装)、亚历山大·罗钦科(男式工装)

男女工装的样板

1920年代

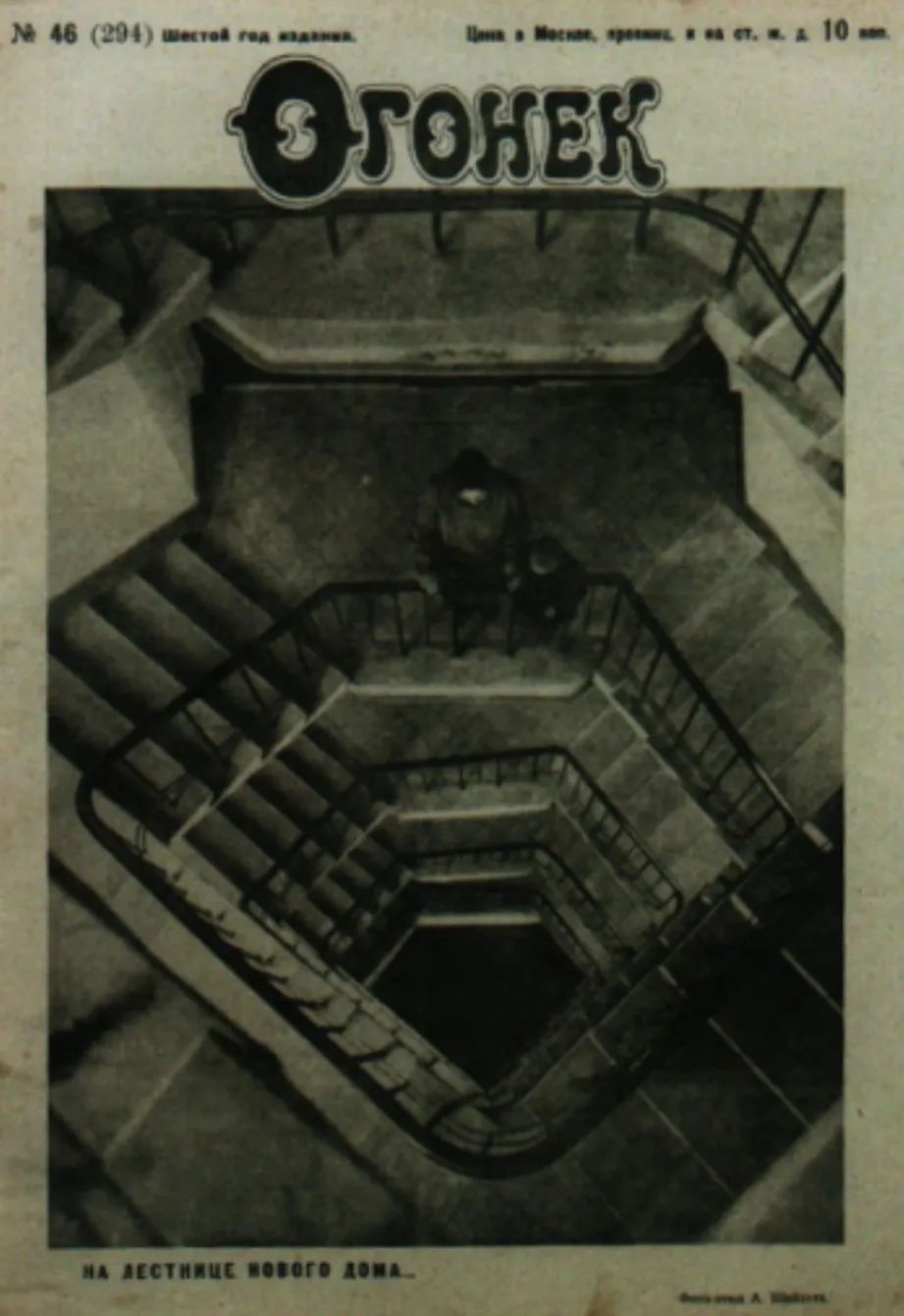

阿尔卡季·沙伊赫特

《星火》第46期封面,出版于莫斯科

1928年

4

日常生活的艺术

THE ART OF DAILY LIFE

大革命之后,社会和家庭的新生活方式在各大城市中形成。当现代主义风格在欧洲盛行之时,同时流行着一种收录家具设计和装饰图片的图录。根据这种形式,1925年《日常生活的艺术》作为杂志《红色涅瓦》附录的小册子问世。册子展示了简练的几何形态的设计范例,如俱乐部的家具、用于展示的讲台、俱乐部和木制阅览室的室内设计以及戏剧服装和节日场景都以双色石印(红与黑——构成主义的用色)的方式被印刷在了36张图版上。这类大众化的日常生活的设计通过便携、装配、功能多样、适应批量生产等特征传达出新型社会的新精神。

After the Revolution, a new way of life for society and the family took shape in the major cities. Inspired by the kind of decorative art albums and portfolios that had been published in Europe during the heyday of the Art Nouveau style, filled with drawings of furniture and decorations as well as examples of interior design, “The Art of Daily Life” booklet was released in 1925 as an supplement to the weekly satirical magazine,“Krasnaya Niva”(Red Neva). Examples of concise geometric design including club furniture, display stands, interiors for clubs and reading rooms as well as theatrical costumes and festival scenery were printed in two-colour lithography (red and black - the colours used in Constructivism) across 36 plates. . This new democratic type of everyday life conveyed the new spirit of the new society through designs that were portable, easy-to-assemble, multi-functional, and adaptable to mass production.

杂志《红色涅瓦》附录《日常生活的艺术》封面 和 内页

1925年

亚历山大·罗钦科(美编)

弗拉基米尔·马雅可夫斯基(责编)

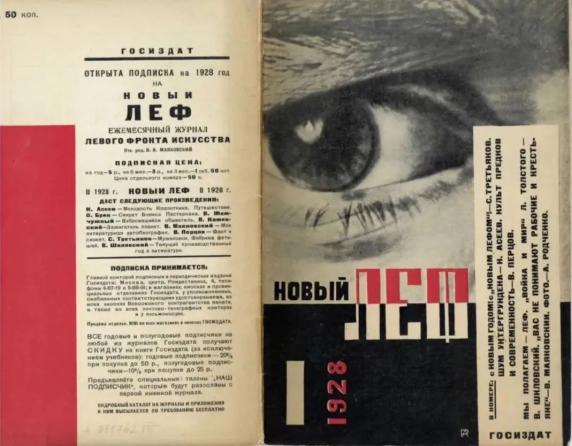

《列夫》第2期,该杂志的主题包括生活的建设、“生产艺术”、“社会订购”理论(即艺术家只是一个师傅,完成各个阶级的任务)、“形式的革命”等

1923年

亚历山大·罗钦科(美编)

弗拉基米尔·马雅可夫斯基(责编)

杂志《新LEF》第1期

1928年

亚历山大·罗钦科

糖罐,茶具系列

1922年

卡兹米尔·马列维奇

至上主义茶具组合

1923年

伊利亚·查什尼克

至上主义图案餐盘

1923-1924年

亚历山大·罗钦科

为戏剧“因佳”设计的折叠椅

1929年

尼·米·苏叶京

“家具超级套装”

1927 年

艾尔·利西茨基

为德国德累斯顿的卫生展设计的D61号椅子

1930年

娜杰日达·拉玛诺娃

为巴黎国际现代装饰艺术和工业艺术博览会设计的套装

1925年

瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃

构成主义日常工作服

1920年代

瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃

“阅读晚会”俱乐部演出演员运动服

1924年

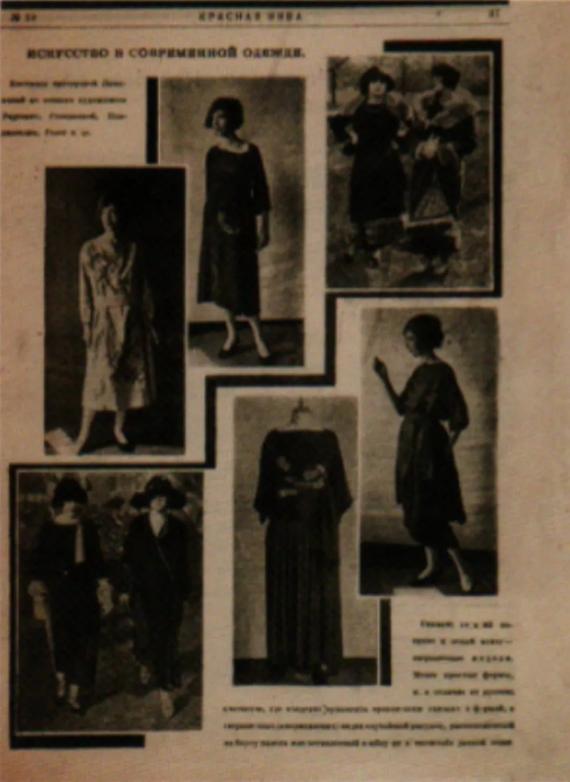

亚历山大·罗钦科、瓦西里·康定斯基、瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃和妮娜·根克

现代服装中的艺术

出自杂志《红色舞台》

1923年第52期

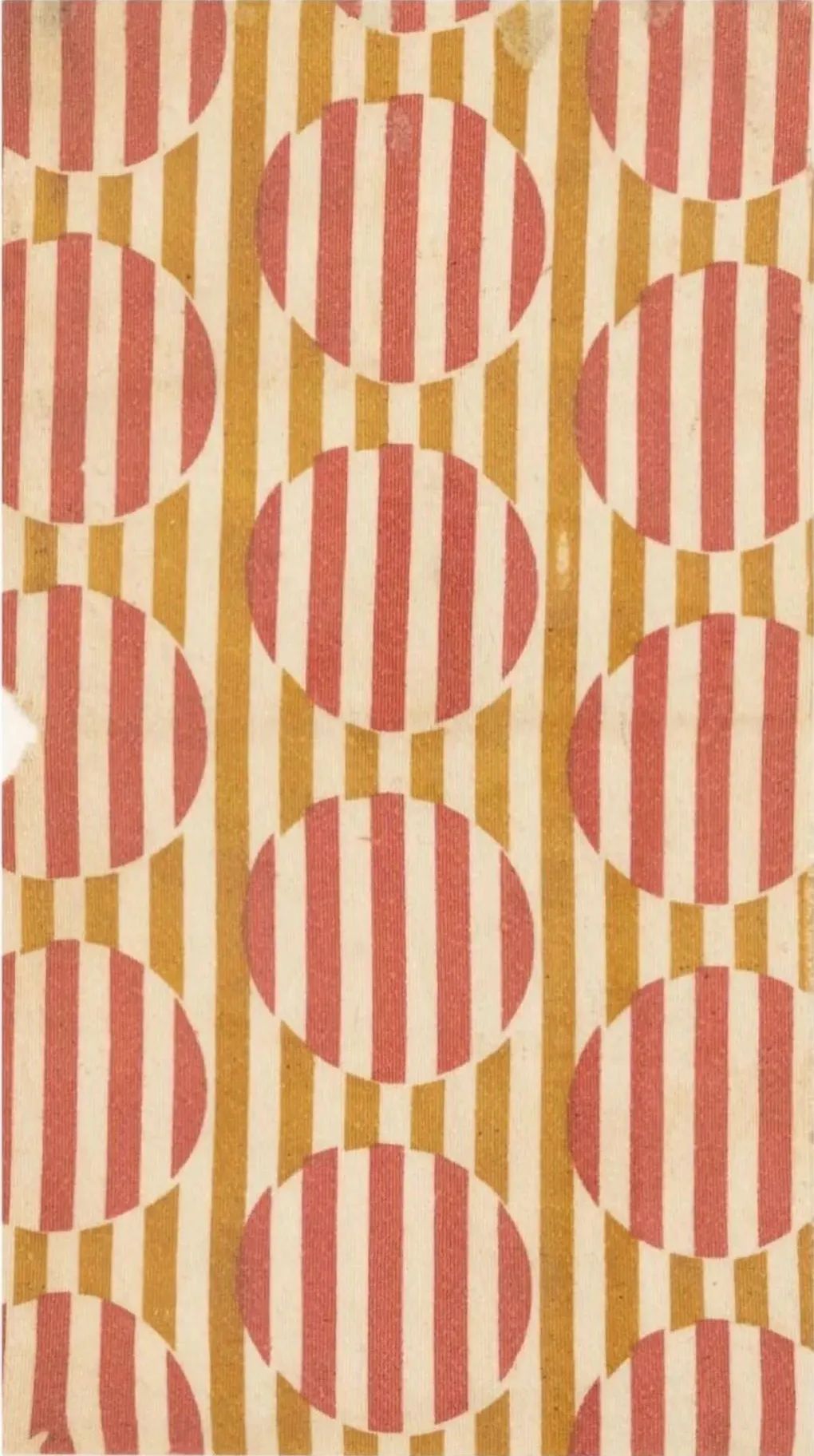

瓦尔瓦拉·斯捷潘诺娃

印花设计

1924年

亚历山大·罗钦科

为国立出版社列宁格勒分社所作的海报“书籍”

1923年

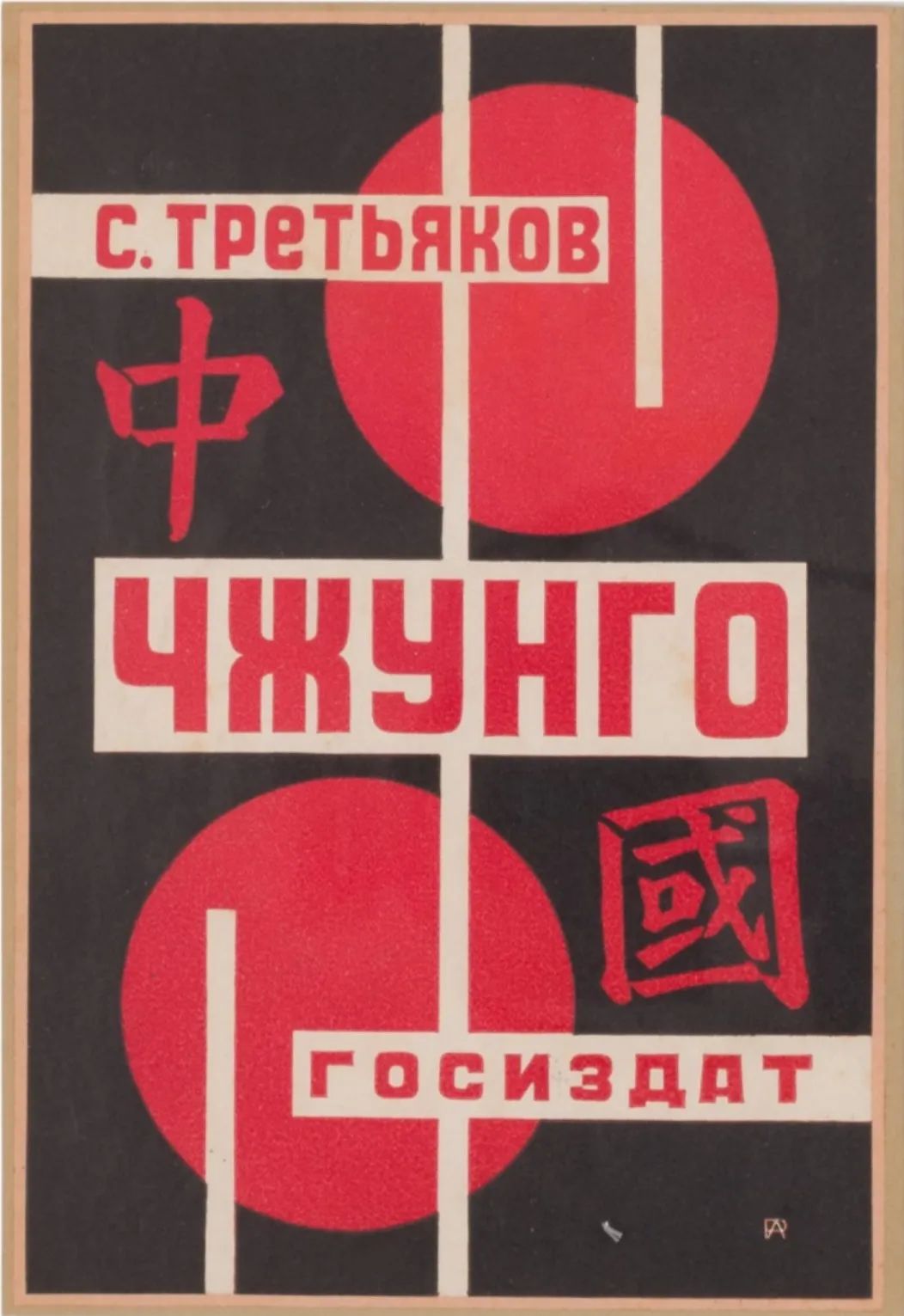

亚历山大·罗钦科

为《中国》设计的封面( “列夫”创作团体的重要理论家之一谢尔盖·米哈伊洛维奇·特列季亚科夫在书中记录了作者在1920年代于北京大学工作时所见到的中国百姓生活)

1927年

亚历山大·罗钦科

国营百货商店(古姆)广告宣传画

1923年

谢苗·谢苗诺夫-梅涅斯

电影“土西铁路”的宣传画

1929年

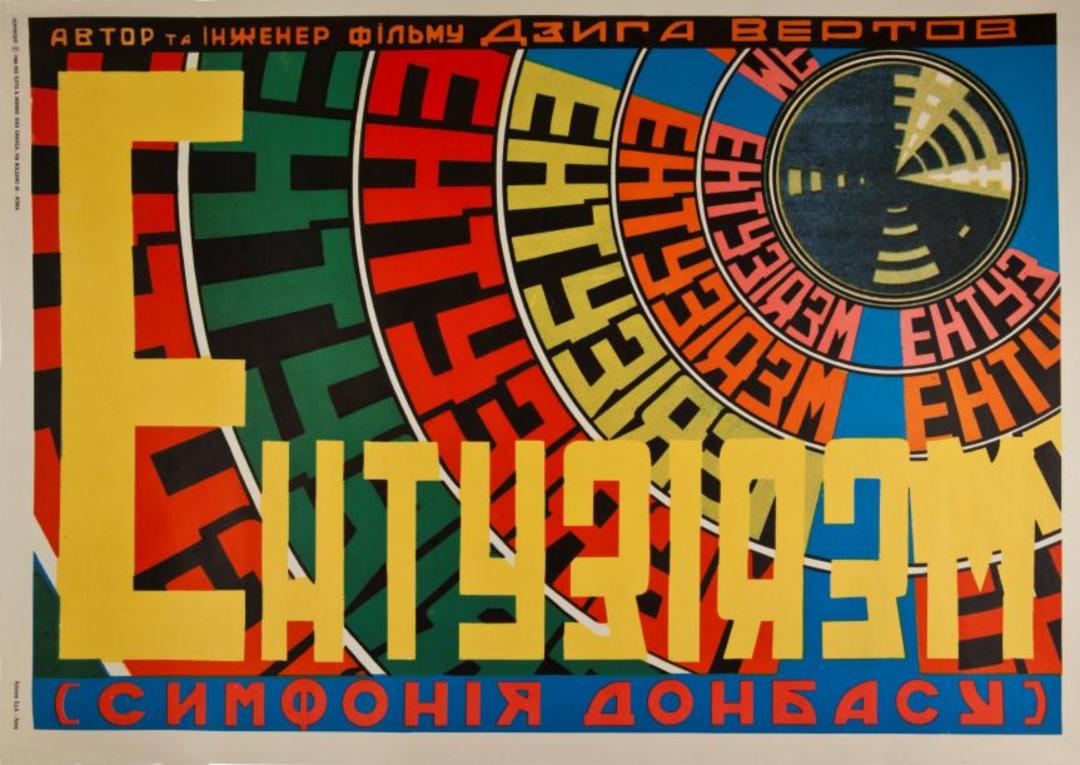

作者未知

济加·维尔托夫电影“热情”(“顿巴斯交响乐”)的宣传画

1931年

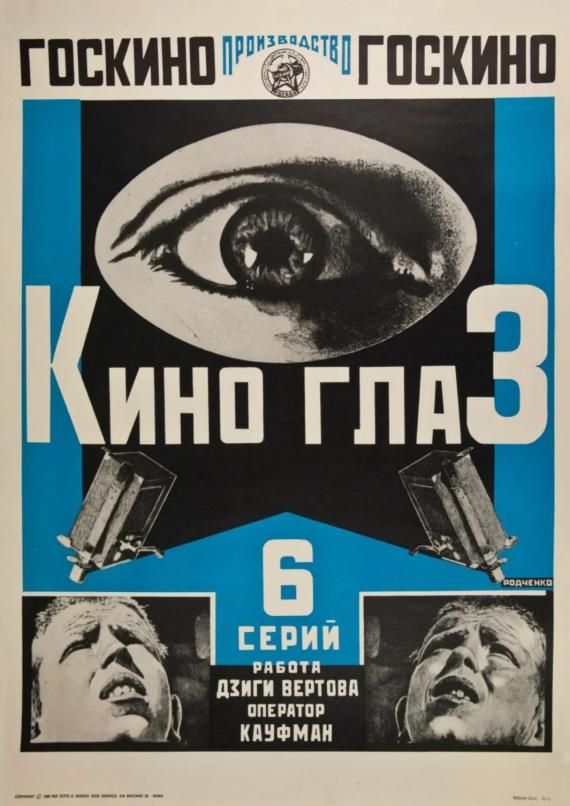

亚历山大·罗钦科

济加·维尔托夫导演的纪录片Kino-eye(电影之眼)的电影宣传画

1924年

5

未来城市

CITY OF THE FUTURE

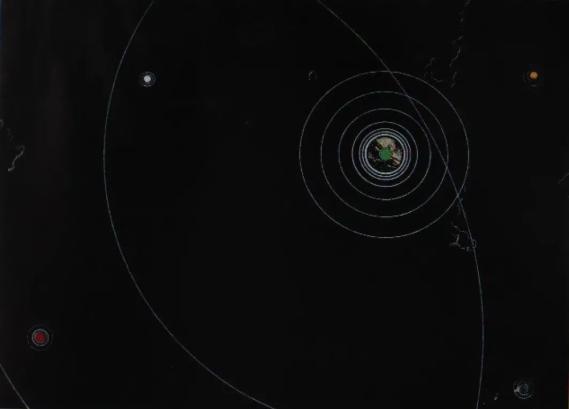

正如塞利姆汗·马戈梅多夫(Selim Khan-Magomedov)所说, 社会乌托邦是人类发展社会正义模式数百年的经验,是要将人从历史各个阶段所伴随的社会不公中解放出来的思想实验室。

苏俄先锋派的建筑和城市设计,在实践中对前人提出的新社会生活模型进行检验和发展。建筑师以“社会设计”为出发点,开发城市新型聚落、住宅和公共建筑,重组社会主义日常生活模式。这些实验的最终目的是为了实现培养“新人”的理想,因此他们更多地关注人的感受,体现出人文色彩。例如,关于城市垂直分区的前卫概念,强调开发人们对于城市“上空”的感知,从而使得其建筑设计的“上立面”呈现了前所未有的形态和审美。从城市的上空到地球的上空,对于人类生活空间的想象从此被打开了。对于技术进步的笃信让他们在规划和建设中大胆超越技术和功利问题,着手设计未来的世界。

As Selim Khan-Magomedov wrote, “Social utopia is the centuries-old experience of mankind in developing a model of social justice. It is the laboratory of ideas that people dream of liberating humanity from the social injustice that accompanies all stages of history.”

The architecture and urban design of the Soviet pioneers tested and developed in practice the new model of social life proposed by its predecessors. Using “social design” as a starting point, architects developed new urban settlements, housing, and public buildings that reorganized the socialist model of everyday life. The ultimate goal of these experiments was to realize the ideal of cultivating the “new man”, so they focused more on human feelings and embodied the human dimension. For example, the avant-garde concept of vertical urban zoning emphasized the development of people's perception of the “sky” above the city, which led to an unprecedented architectural form and aesthetic for the “upper façades” of high-rise buildings. From the skies over the city to the skies above the earth, the imagination of human living space had been opened up. Their faith in technological progress led them to venture beyond technical and utilitarian issues when it came to planning and construction, and to ultimately design the world of the future.

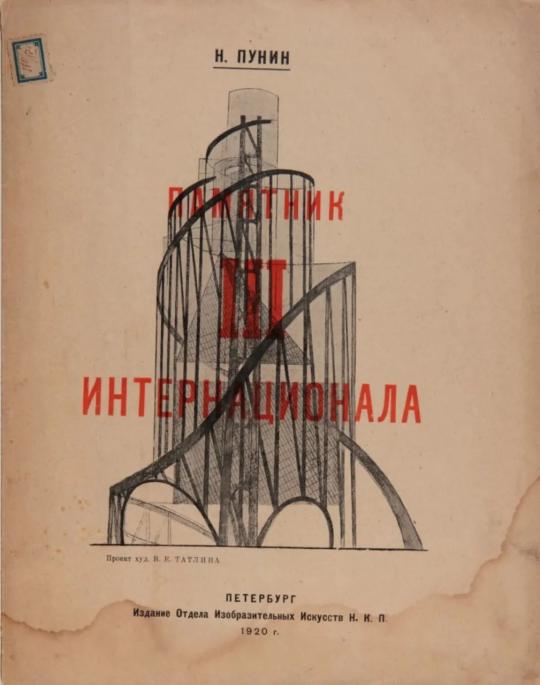

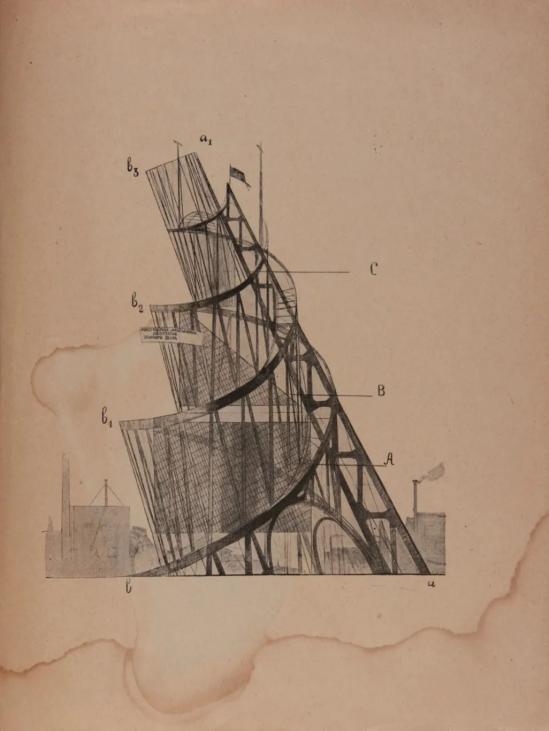

弗拉基米尔·塔特林

《第三国际纪念碑》封面和内页

1920年

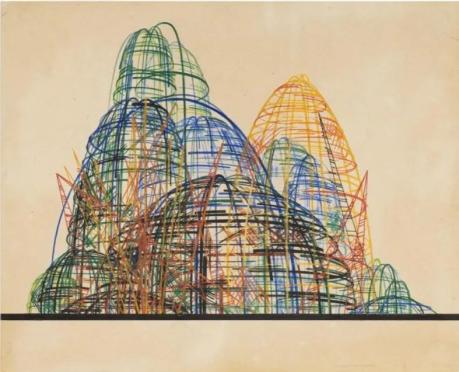

卡兹米尔·马列维奇

至上主义建筑原型(Architecton)

1925-1927年

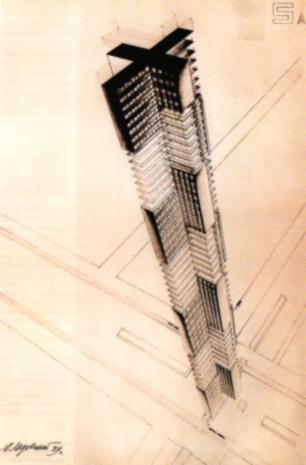

埃尔·利西茨基

水平的摩天大楼

1923—1925年

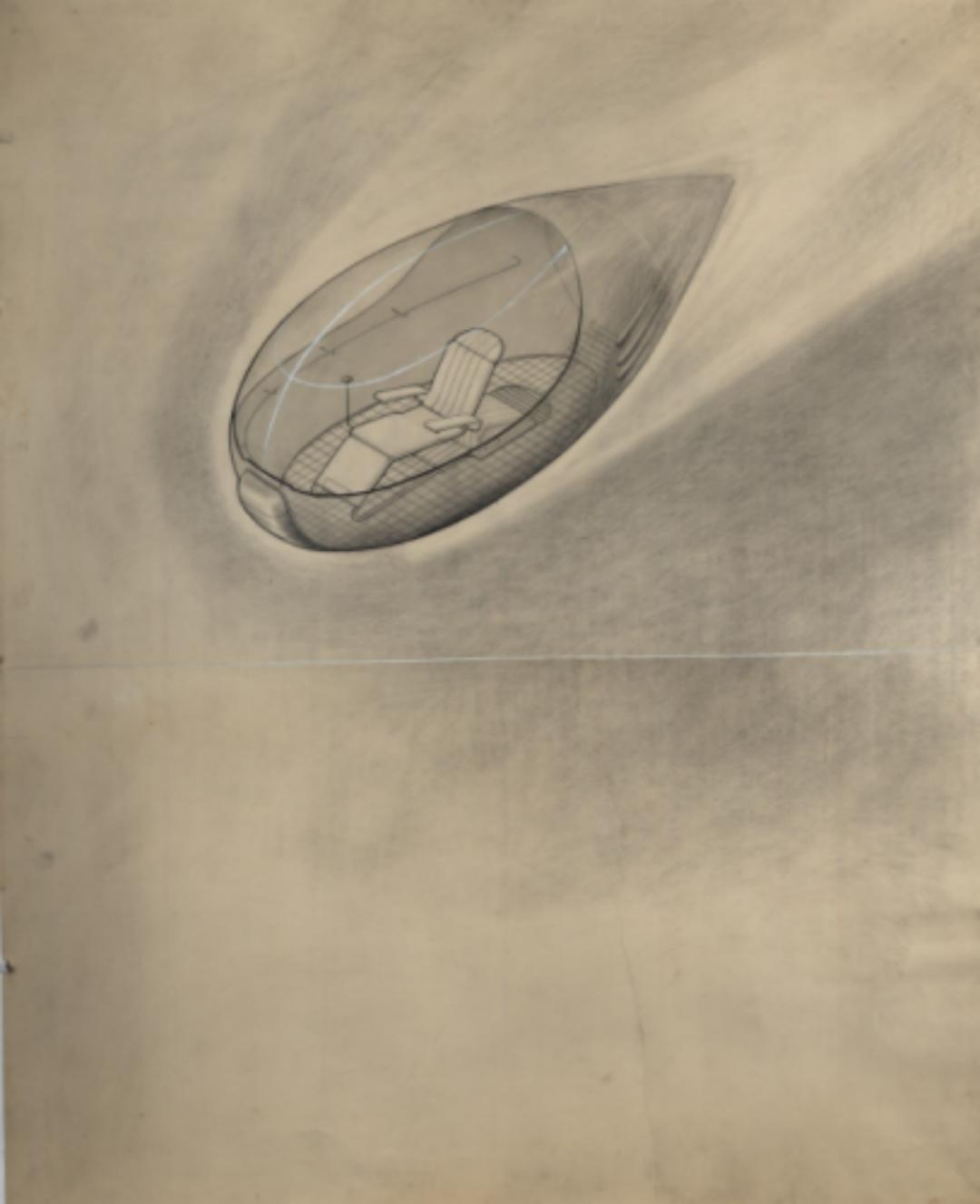

格奥尔基·克鲁季科夫

《飞翔之城》/《未来城市(城市建造与住宅规划中建筑准则的革命)》设计图

1928年

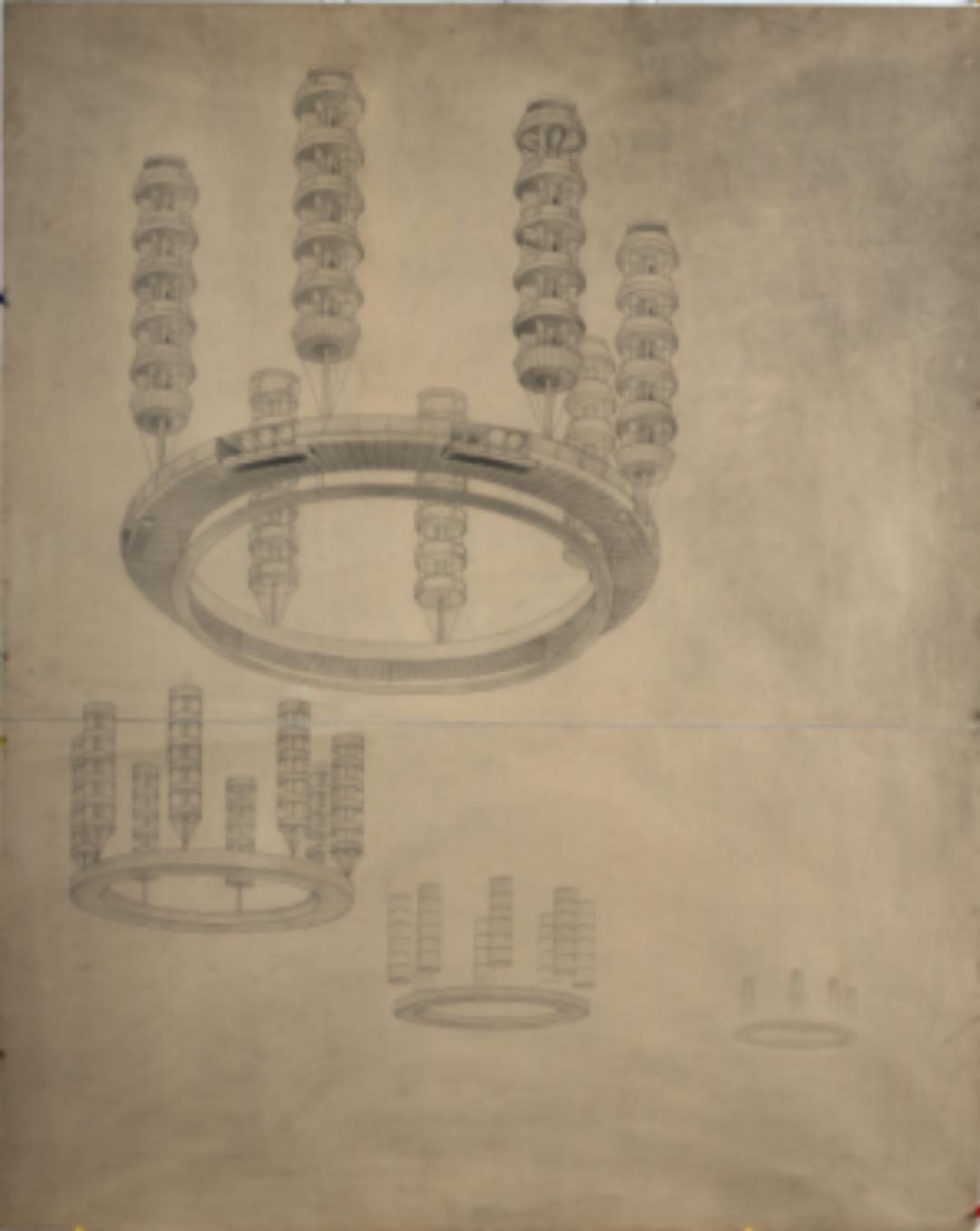

伊·伊·列奥尼多夫

“一种全新的社会俱乐部”空间文化组织方案,项目

1928 年

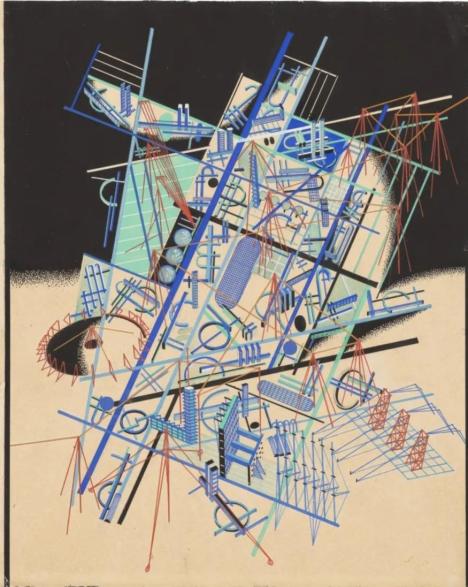

雅科夫·切尔尼霍夫

《建筑幻想》系列之第236号作品《剧院的彩色构作》

1929-1932年

雅科夫·切尔尼霍夫

《建筑幻想》系列之第89号作品《线性序列的空间构成》

1929-1932年

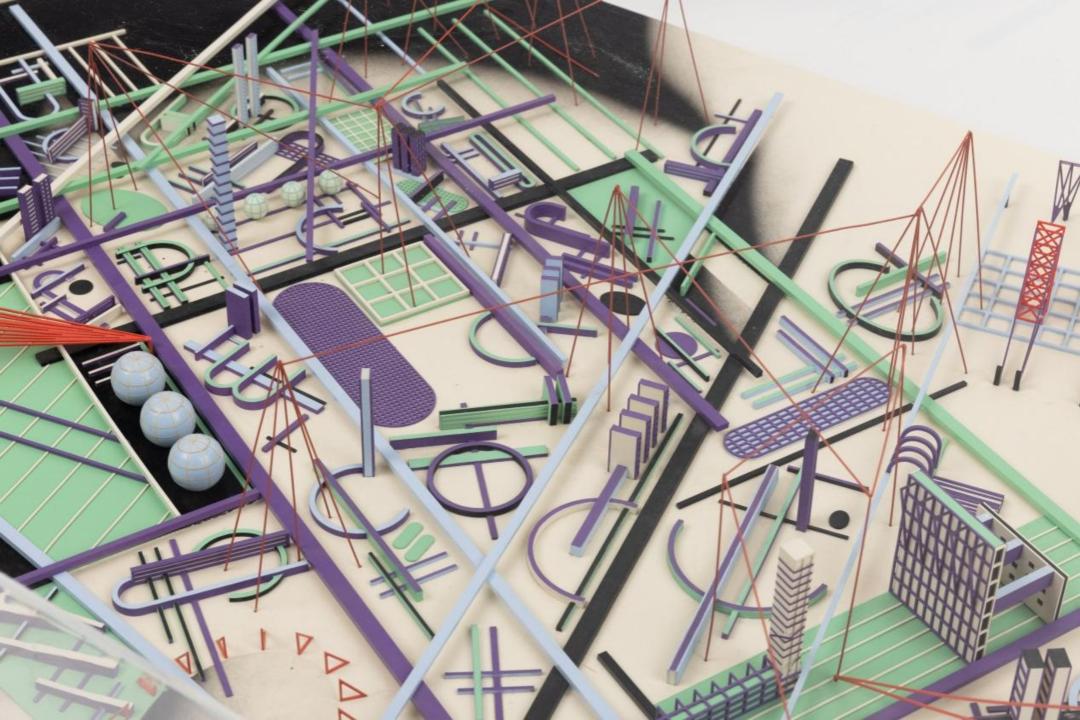

雅科夫·切尔尼霍夫

《建筑幻想》系列之第87号作品《音乐建筑的构成想象》

1929-1932年

雅科夫·切尔尼霍夫

《建筑幻想》系列之第87号作品《音乐建筑的构成想象》模型

1934年

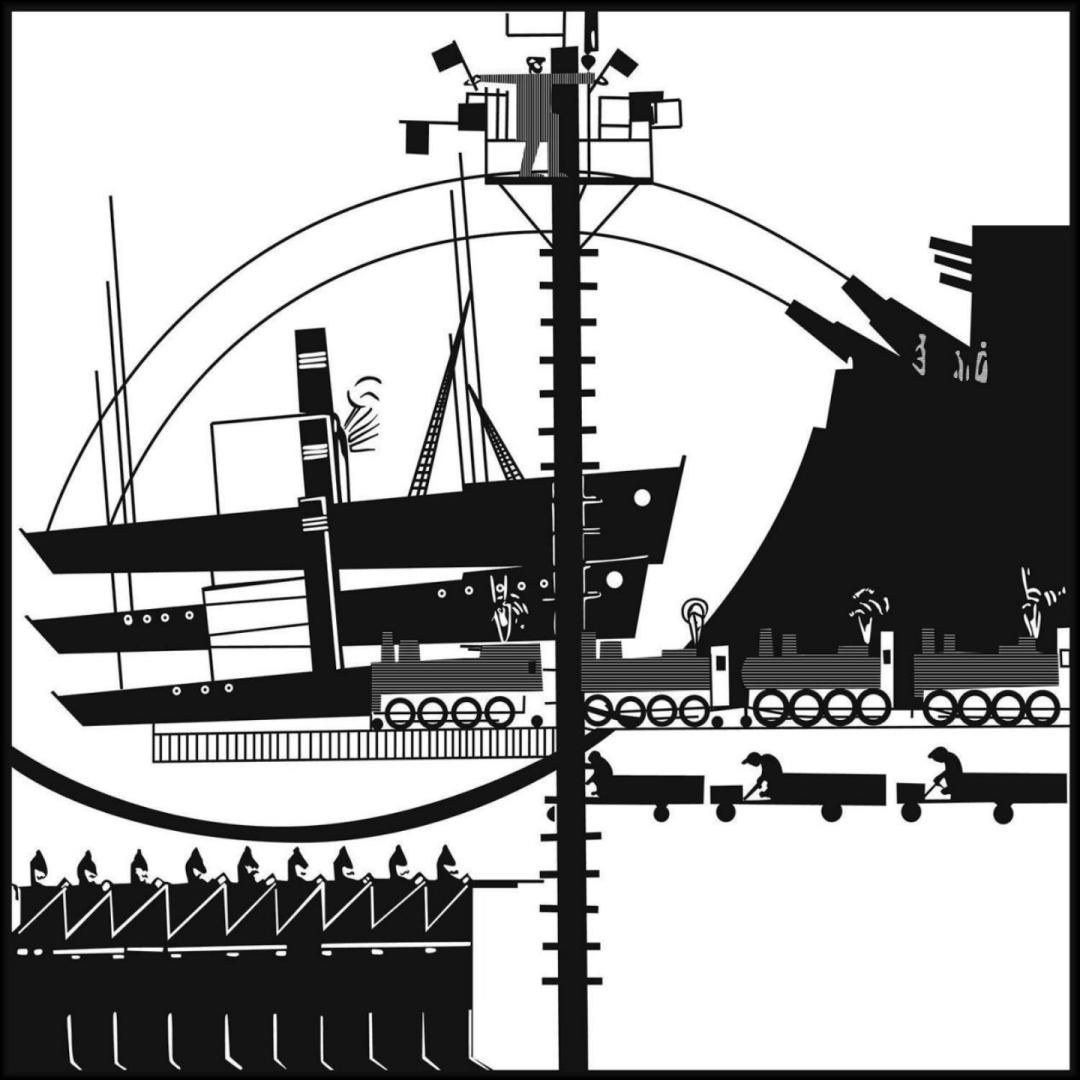

阿尔塞尼·阿夫拉莫夫

城市交响乐“警报交响曲”,Gorn,第 9期,1923

1922年

弗拉基米尔·舒霍夫

“舒霍夫塔”——莫斯科共产国际第二广播电台(沙波洛夫无线电中心)

1920-1922 年

莫伊谢伊·金兹伯格,伊格纳蒂·弗兰茨维茨·米利尼斯(建筑)

谢·利·普罗霍罗夫(工程)

独立住宅及向公共住宅的过渡——“纳康芬公寓”

1928-1930年

阿·伊·梅什科夫, 尼·米·莫洛科夫, N.A. 谢尔巴科夫, 亚·尼·沃尔科夫

“莫斯科“乌萨切夫卡——小丘”定居点乌萨切夫卡住宅建筑群内院”

1925-1928年

伊·谢·尼古拉耶夫

莫斯科大学生公社的住宿楼、大堂和大教室

1929-1931年

尼·亚·拉多夫斯基

“多米尼加共和国圣多明各哥伦布灯塔纪念碑”

参赛项目轴测图

1929年

维·亚·维斯宁,尼·雅·科利,S.G.安德列夫斯基,G.M. 奥尔洛夫

“乌克兰苏维埃社会主义共和国扎波罗热第聂伯河水电站”项目

1927-1932 年

P.I. 伏罗洛夫

“乌克兰苏维埃社会主义共和国哈尔科夫市自动电话站”,1930-1931 年

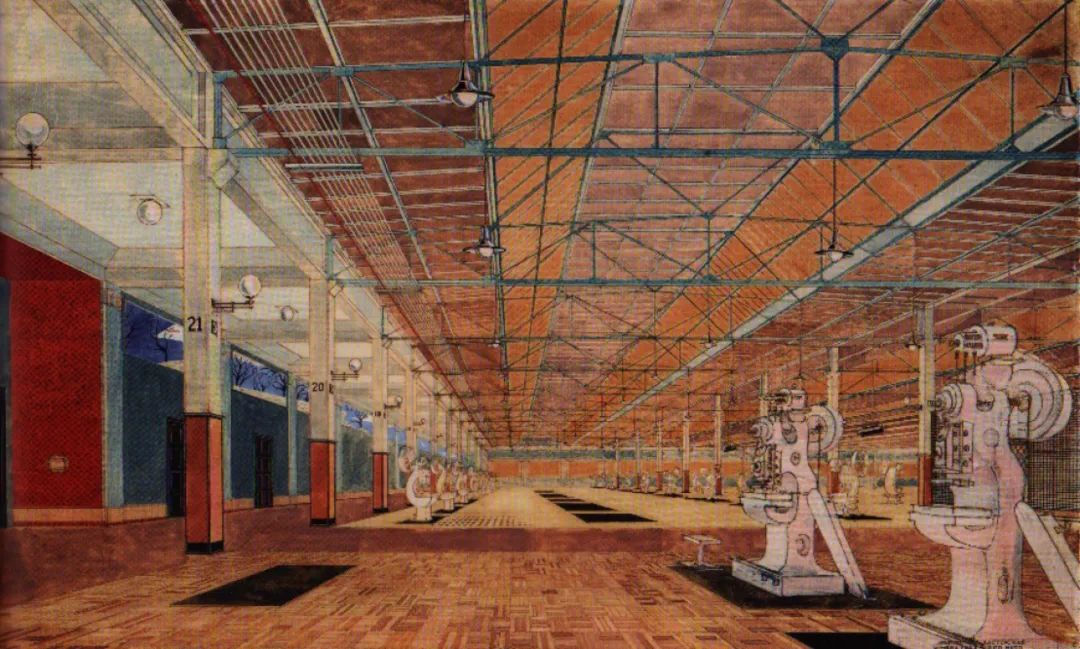

安·斯·费先科(负责人),A.V. 科罗特科夫, S. 尤索夫, 列·鲍·维利科夫斯基, B. 瓦尔加辛,工程师 А.А.瓦尔加,Н. 古谢夫

“莫洛托夫高尔基汽车厂加固型散热器大楼内景”项目

1935 年

N. 米申科(封面设计)

《第聂伯建筑公司与新扎波罗热》,第 2 期 / 编辑:B. 利佐娃,哈尔科夫

1932年

展览开放信息:

由于疫情限流原因,特展“从呼捷玛斯到未来图景——苏俄设计历史”之前仅作为内部观摩。自开幕的一个多月以来,该展受到了专业界的广泛关注和认可。应广大观众的要求,设计馆决定自2022年5月18日开始,面向所有观众开放。

参观须知:

疫情期间,该展目前仍限流开放,同一时间段人流量最多为60人,请错峰参观。参观前请点击“中国国际设计博物馆CDM”微信公众号实名预约,根据防疫要求,不接受团队预约。

个人预约电话|0571-87200881(博物馆前台)

散客公众导览安排|逢周六、周日| 上午10:00 ,下午13:30

来 源 |中国国际设计博物馆

编 辑 |刘 杨 赵雨岑 梅祎涵

审 核 |丁剑锋 张春艳

投稿邮箱:caanews@caa.edu.cn

出品:

中国美术学院党委宣传部

PUBLICITY OFFICE OF THE CPC CAA COMMITTEE

中国美术学院新闻中心

CAA NEWS CENTER

CAA融媒体工作室

CAA MEDIA CONVERGENCE CENTER

原标题:《5·18国际博物馆日|特展“从呼捷玛斯到未来图景——苏俄设计历史”》

本文为澎湃号作者或机构在澎湃新闻上传并发布,仅代表该作者或机构观点,不代表澎湃新闻的观点或立场,澎湃新闻仅提供信息发布平台。申请澎湃号请用电脑访问http://renzheng.thepaper.cn。

- 报料热线: 021-962866

- 报料邮箱: news@thepaper.cn

互联网新闻信息服务许可证:31120170006

增值电信业务经营许可证:沪B2-2017116

© 2014-2024 上海东方报业有限公司